There’s a marvellous passage in Rachel Cusk’s latest bizarre and dreamy novel, Second Place, and it concerns a period of great change in the thoughtful narrator’s life. She writes, of meeting her second husband Tony:

[H]e was so diminutive and self-contained, not at all the sort of man I myself might be physically drawn to […] [he] also awoke me, but to the presence in myself of a fixed male image, to which he did not correspond […] To see him, I had to use a faculty that I did not entirely trust. All my life this image, I came to realise, had in various forms caused me to recognise certain people and to consider them real, while others remained unnoticed or two-dimensional.

She goes on to note:

I understood that I should no longer trust it, and the mechanism of not trusting and not believing and then being rewarded for it came over time to supplant my actual trust and belief: this, I think, more than Tony himself and more than the geographical distance from my previous life, formed a great part of the gulf separating me from the person I had been.

This was — beyond being just a fine specimen of craft — one of the first descriptions I had ever read of that eerie but unmistakeable force that had driven so many decisions in my own life: the sense of reality.

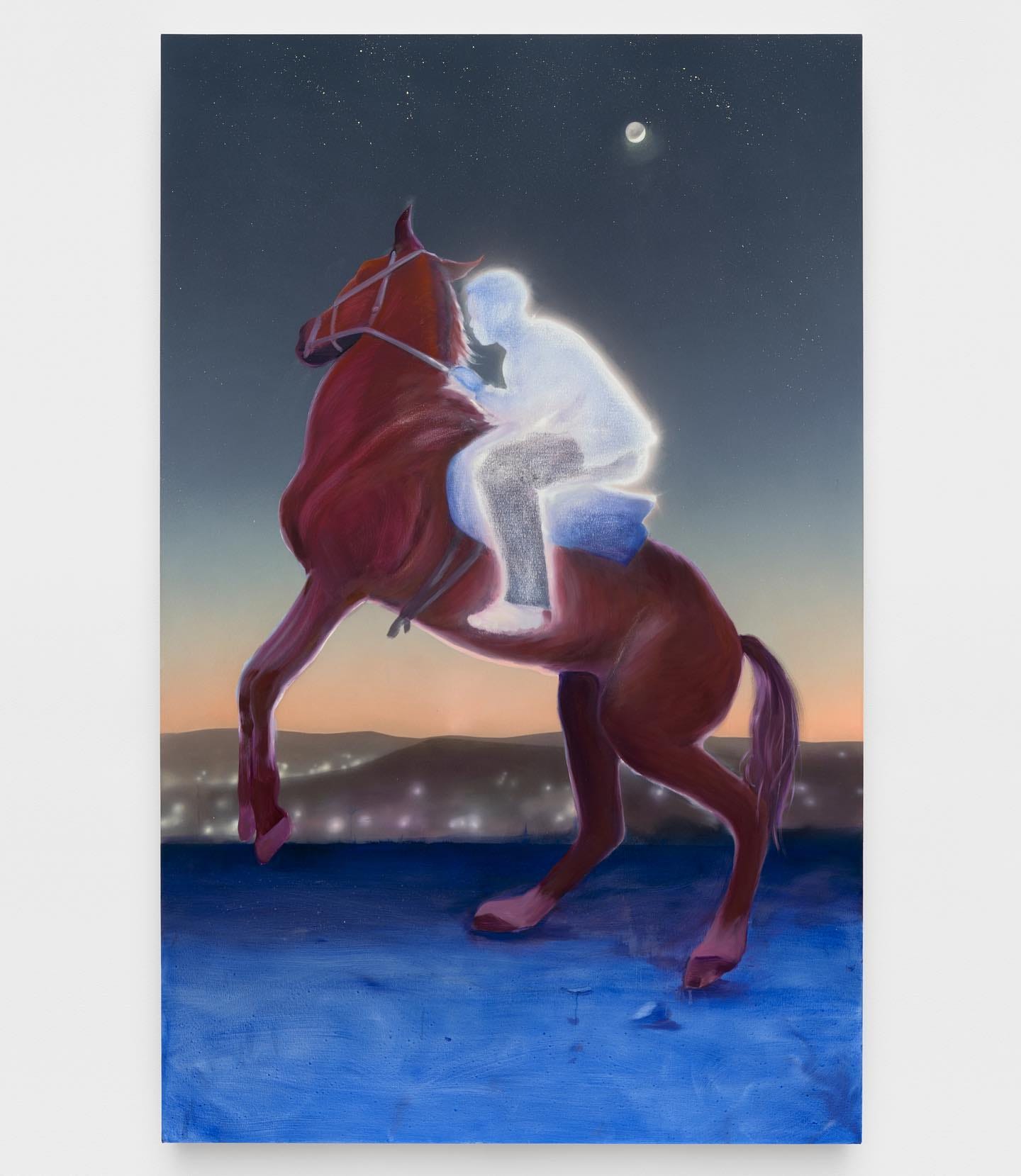

I was reading Second Place exactly a year ago, in a charming but tattered apartment on the East End of Toronto. I was still dating my then-partner J, and often slept on a little pull-out futon in the living room under a full wall of south-facing windows. At night, I’d watch the moon weave in between boreal clouds like a weary eye, nodding off to the British audiobook reader’s voice in my ears as the sky became clear with cold. A blue so deep it looked frozen to death; a sky so flat and factual it seemed almost confrontational; these visions bookended my days like silent heralds of the loneliness to come, uninterpretable. Trouble in love always seems so temporary — then the house falls all at once.

I began dating J rather quickly after we met, not just because things between us seemed so light and functional, but because of how easily he seemed to understand me at first— it seemed to me then that the project of building a life with another person was one accomplished chiefly through the medium of language. I suppose I imagined that in the trials to come, we would triumph by telling each other — in great detail — what we hoped would be accomplished, and how, and by whom. The doing, I presumed, would be easy. The telling was all that mattered.

As it turns out, telling is paltry when two people cannot, fundamentally, get along. We wanted different lives — and this was a fact so apparently evasive to us, so serpentine and sly, that it took us nearly three years to figure it out. Along the way, we moved house three times, saw through the painful death-throes of a community house I had co-founded nearly half a decade ago, and signed the witness papers of his best friend’s wedding as the Pacific heaved behind us. By the time it was all over, I felt so whittled down by life itself that I was worried I’d get lost in the wind somehow — a wood shaving, an earring, a crumb.

I know that relationships end all the time, and our age represents nothing if not the right of the individual to pursue his own purposes. All the same, I had not really expected this particular relationship to end. I imagined it continuing ad infinitum for the same reason that I had begun it at all: because it seemed to me to be thoroughly real, almost painfully plausible. I believed, because our relationship seemed so believable, that it was meant to last.

The opposite of the phenomenon I am tracing here is reasonably well-known in works of fiction. This is the feeling of something — usually a relationship with a beautiful but flighty, intense woman — being “too good to be true.” The usually-male protagonist skips down the sidewalk; bluebirds chitter encouragingly; he sings, he taps his heels together, giddy with disbelief.1 In such narratives, there are usually two possible endings: either the protagonist's intuition proves true and his picturesque life is devastated by some unforeseen disaster -- or he is rewarded in his flight of mad daring, and said to live happily ever after with his inconceivably hot wife. Both versions of this story possess the structure of a fairytale; they are forms of cultural wish fulfillment that we repeat precisely because they seem so otherworldly.

In reality, as we are often told, we ought to seek contentment in love: seek those who make us feel like ourselves, who make us feel “at home.” If we are to spend the rest of our lives in the arms of another, after all, we ought to make sure those arms are mighty comfortable. These people, when we meet them, feel immediately familiar — as though we might have known them our entire lives. They fall, as if by ritual magic, into the same scripts we have inherited in love, repeating the same lines we have always expected to hear, knowing the moves to the dances we learned as children. In the light of what we have always known, these people appear somehow more real than their stranger counterparts — more solid, somehow, more plausible. We trust that they are what they say they are, because we have been with them before.

In J’s case, the “sense of reality” came through his language, comfortingly Midwestern; he seemed to come out of the cold earth I had known as a child. He teased me, often, and seemed to have in his mind this affectionate image of me as some flighty fairy, some hopeless art-filled wunderkind who would otherwise float away. He paid the bills and often did the dishes, and even though I could join him, I often didn’t; I wanted to stand in the kitchen and discuss ideas. If I was the strange druid who could survive on mere chlorophyll and language, he was the practical-minded man I had always thought I would need: steady, undramatic and just the slightest bit critical. This feeling for me, of being the “misunderstood artist,” had been such a mainstay of my own coming of age that I had come to believe it represented some sort of fundamental truth about the world. I was comforted, in a way, when he did not understand me — because I did not expect to be understood. I was comforted by his face, too, which I found to be both beautiful and ordinary, perhaps beautiful because it was ordinary. More and more, our relationship came to correspond with the image I had carried of the life I was “supposed” to have. I fell in love, then, the way erosion befalls a steep hillside: with a gravity so fatal that slowness seems irrelevant.

The trouble is, the “sense of reality” may have little to do with the solidity of reality itself.

It is a cliché at this point, at least among my Millennial generation, that we do not automatically seek what is good for us in love, but rather what is familiar. I think this adage ought to extend not merely to romance, but to almost all aspects of life: the job we choose, the place where we settle down, our aspirations and our worries, our sense, in the final instance, of who we really are. It seems that this may even emerge most basically from our sociality as a species; if we want to belong, after all, it rather behooves us to believe what others say about us. Soon enough, these beliefs — oft-repeated, or at least lived out — become our sense of reality. Perhaps this even underlies those seemingly disjointed beliefs we sometimes encounter in our friends (“Wait… you think you’re not attractive/intelligent/kind enough?”) rather readily: the beliefs become, in a way, artifacts of a community our friends once wanted to belong to.

It isn’t, then, that we particularly want to be in relationships / jobs / situations that make us feel a certain way (say, inferior). It’s rather that feeling a certain way (say, inferior) carries with it a feeling even more important than our own sense of esteem: a feeling that the world is real, and that we are tethered to it, and that we have a place in it. We would rather, it seems, have a painful place to live than no place at all. The former, we tell ourselves, is eminently more survivable.

Thus, in love: it is said and observed that if one came of age, say, in a chaotic household, one finds oneself intuitively drawn to a chaotic partner. It seems to me that we imagine the primary mechanism of this phenomenon to be attraction — to the rush of exhilaration we feel when the outlaw enters the bar, jeans ripped and revolver half-tucked. But it seems to me that there is another force at play, and it is both more tragic and more ordinary: people desire to live in a world which makes sense. The sense that one is actually living in reality — that one’s life is real, that is has meaning, substance, heft — may be more important than finding happiness in love. It isn’t the beauty of the outlaw, then, that gets us in the end — it’s the feeling that we ought to be, somehow, on the run. That we always imagined our life as a fugitive. The handsome stranger in the bar is merely a vessel for the story we have already found ourselves living in.

When things ended with J, I was cast into a time of great uncanniness. Uncertain about where I would live, and to some extent, what I would do, life fell out of favour with me. If, before, everything in my life had a certain face, and it turned towards our togetherness, now even the bedside lamp seemed cold and alien — a thing without intention, without purpose, neither animate nor inanimate. This feeling — that I no longer belonged to the world itself, that we no longer seemed to recognize each other — seemed to me to be worse than the grief I also felt, because the grief I understood to have an end. I worried, on the other hand, that I might feel out of place forever, and I would never make my way back into a world in which things were in proper relation to each other.

In one of my favourite essays of all time, the legendary novelist Haruki Murakami writes about a shift he experienced in the reception of his works around the time of the new millennium:

There has been an especially noteworthy change in the posture of European and American readers. Until now, my novels could be seen in 20th-century terms, that is, to be entering their minds through such doorways as “post-modernism” or “magic realism” or “Orientalism”; but from around the time that people welcomed the new century, they gradually began to remove the framework of such “isms” and accept the worlds of my stories more nearly as-is. I had a strong sense of this shift whenever I visited Europe and America. It seemed to me that people were accepting my stories in toto — stories that are chaotic in many cases, missing logicality at times, and in which the composition of reality has been rearranged. Rather than analyzing the chaos within my stories, they seem to have begun conceiving a new interest in the very task of how best to take them in.

The essay, called “Reality A, Reality B” is about the very shift in the fabric of reality that seemed to occur in the Western world around the time of 9/11. Murakami argues that this was a culturally cataclysmic event — not just because of its implications for geopolitics and war, but also because of the way it subtly transformed the way that reality itself was experienced:

Let’s call the world we actually have now Reality A and the world that we might have had if 9/11 had never happened Reality B. Then we can’t help but notice that the world of Reality B appears to be realer and more rational than the world of Reality A. To put it in different terms, we are living a world that has an even lower level of reality than the unreal world. What can we possibly call this if not “chaos”?

In a Murakami novel, things and people appear and disappear without warning; strangers arrive to give gnomic pronouncements, advice or packages to be delivered; furtive sex happens in mountain retreats with lovers who disappear with the morning mist. Best of all, all of these things happen to a narrative protagonist with a signature “Murakami deadpan” — who remarks upon these things as one might remark upon everyday happenings at a grocery store.

If Murakami’s writing has been remarkably consistent over the years — both in theme and tone — it is the world itself that has changed. We expect the news not to make sense, to appear to us as a clipping from some surreal dystopian universe. We expect the stock market to dance and the rent to rise. We expect the world, fundamentally, to be unlivable — and we do not expect to belong. Our very planetary connection — our sense that, to some degree, we belong on the planet Earth — is continually threatened by technologic greed, and we sometimes struggle with shame for even existing. It would be better, we sometimes think, to not have existed at all.

Today, love may be one of the last places my generation seeks to look for the “sense of reality,” the very last stop on the line, as it were. After love, there may be no more refuges for meaning.

The romantic ideal of love — and with it, the idea that we ought to follow our personal intuitions and emotions when choosing a life partner — is a relatively recent historical phenomenon in Western civilization. It dates back no further than 300 years. As the wisdom went, freed from the shackles of economic expediency and societal mandate, romantic love would become the new engine of human happiness and flourishing; free to choose, we were bound to choose well, and to the chief advantage of ourselves and those around us. Many of these ideas are happily operative in canonical dating advice today — the idea of trusting one’s own intuition, looking for a spark, or eschewing the advice of family and friends when finding a true love match. Above all, we believe — just as the first romantics did — that love is primarily a feeling, and that it happens to us, and that we ought to yield to it as a mortal yields to a benevolent divine force.

I do not pretend to pass judgement on any particular paradigm of thinking about love, but I do wish to report that this ideal has held a very prominent role in my own unhappiness. I have indeed trusted my own intuition when it came to love — over and over, in fact. And each time, my intuition led me not to the home I hoped for, but to one it seemed I could never escape. To say that love is a feeling, after all, is to abdicate responsibility for what one does in the throes of such a feeling; one is compelled to date certain people, and not others, merely on a daft calculus of emotional force. It turned out, at least in my own life, that the romantic ideal actually narrowed my sense of choice — and I found myself in the same kinds of love stories, with the same kinds of endings.

Looking back, I wish I had known what I was actually being called upon to do: to bear the discomfort of living in an alien world, in order to eventually become familiar with what would make me happy. To make joy seem normal, I was being asked to leave behind a world of coherence, a world in which I already had a place. It seemed — and still seems to me now — I was being asked to give up the world entire. For some, it may be that real love cannot come without such a sacrifice.

Is this the real risk at the center of love, then? Not the risk of having one’s heart broken, or of being abandoned or disappointed, but the risk of finding oneself torn asunder from the stars — unable to know what is good and right, what is believable and what is utter fantasy? I think of Cusk’s narrator, who describes being unable to believe in the fundamental reality of her husband Tony — and the practice of being rewarded, over and over, for not trusting her own intuition. When I try to imagine myself torn from my own intuition, numb and blindly following my joy, I imagine it as a kind of death — a kind of total remaking of the self. Frankly, it is terrifying. And yet I see no alternative anymore.2

In this light, perhaps we ought to be grateful that our little domestic fantasies come to an end. That verisimilitude has it limits, and the play must eventually close. Perhaps the sooner we come to accept this, the sooner we endeavour to meet each other in the chaos that is — and seek to form new senses of what Reality is, however temporary, however slight. To live in a world that seems to us, on some fundamental level, real — this too may become an artifact of historical processes that have already begun to change.

What good will our fear do us now?

How much better it seems, to try with great sincerity to open our eyes…

Without romance, anchor or center…

In the great Wherever-We-Are…

These things at the limits of reason, nothing at the limits

of dream, the dream merely ends, by this we know it is the real

That we confront

— George Oppen, “Route”

If you liked this essay, you might enjoy this one on the presence of the body in writing, this one on desire, or this one on feeling things deeply.

Paid subscriptions don’t get you anything new (yet) but are a wonderful way to support the work. Thank you to all who continue to support me, in ways both old and new, monetary and otherwise.

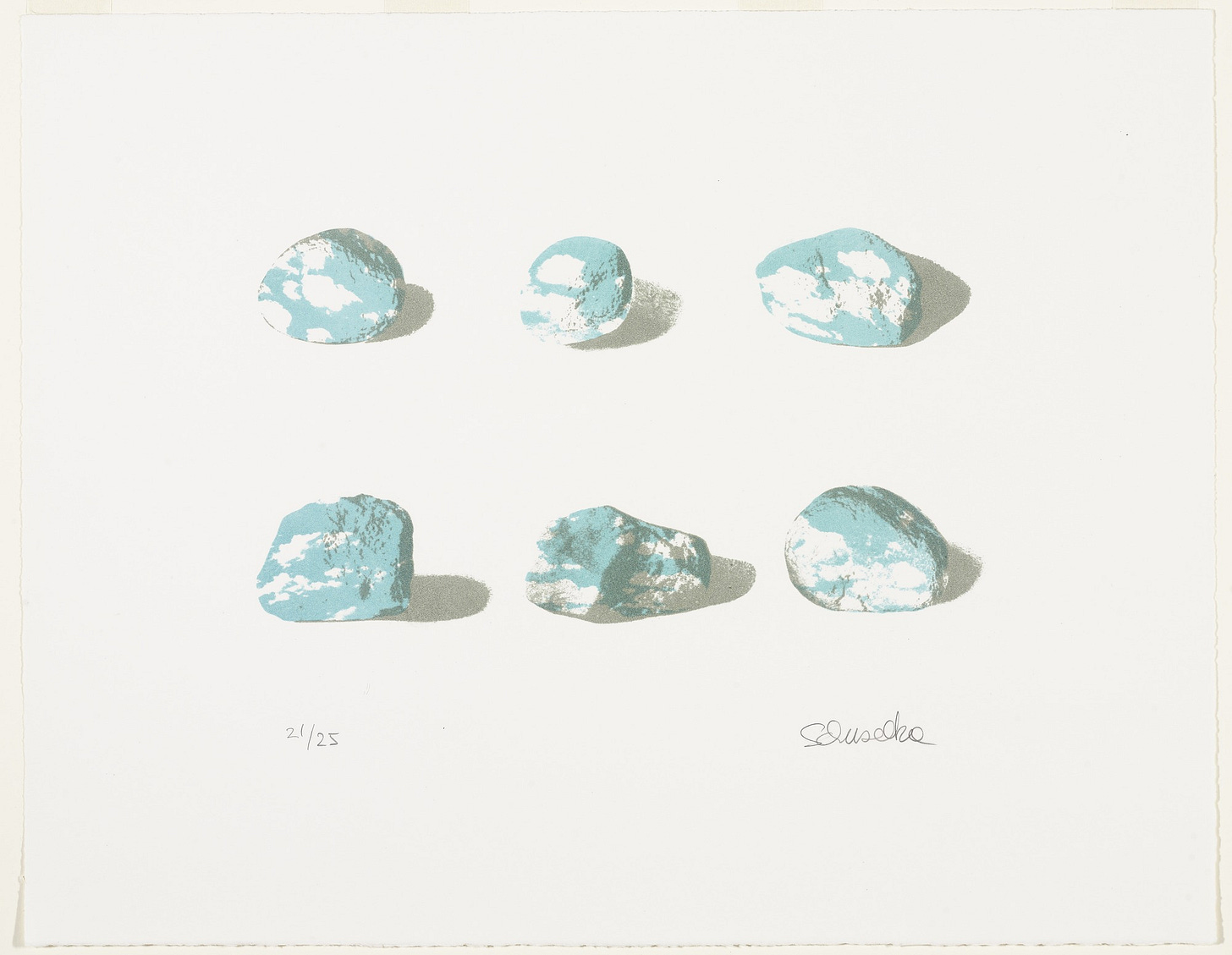

Finally, a variation on my “Memory of Justice” essay has been published in the Are.na 2023 Annual. Much more importantly than this, the Annual features some pretty incredible essays, including one on the One Direction fandom (!) and another about Tchaikovsky. Click on the cover below to purchase it:

Discussion Questions

Feel free to reflect by yourself, with loved ones, or with other readers in the comments.

Do you trust your instincts in love? Why or why not? How has that changed over your lifetime?

Do you feel that the world you live in is real? Why or why not? Has this feeling changed over your lifetime?

Have you ever had to choose between something being familiar and something being good for you? What was it like?

Do I write here of the iconic scene from 500 Days of Summer? Yes, I do.

When I frame the choice for myself this way, I feel great compassion for the tides of regression in the world. One can think of the basic impulse in cultural conservatism as a desire to hold on to the world’s coherence — whereby one’s measure of political extremism is what one is willing to sacrifice in order to preserve such a coherence. In each case, it is not merely that a certain value system is beautiful, right or good — it is also that the lack of any value system, however temporary, is utterly terrifying. In fiction, we call this terror “cosmic horror”: the feeling one gets in the face of a fundamentally meaningless universe.

Vividness is not exclusive to, presumably, real and unreal realities; the emotional spectrum, it seems, remains intact. (The realest experiences of my life feel surreal to me now. In some cases, I've felt most real as an individual is in an unreal environment (Thus, the misunderstood)). Your comment about turbulence in love, being just that---turbulence before the plane assuredly lands---caught me off guard. I've always been comforted by the temporary nature of life. Now, I'm beginning to appreciate the phrase in context. People often say, to comfort or dismiss, that everything is temporary; nothing lasts forever. However, it forgoes the monkey-in-the-middle between now and always: now and yet.

An exquisite blend of biography and observation. The dictionary definition of ‘essay’ could contain a link to this piece. Would love to see an essay-length expansion of the second footnote.