“Beauty is terror. Whatever we call beautiful, we quiver before it.”

- Donna Tartt

Recently, on an extravagant bike ride through High Park and along Lake Ontario, my friend had us stop on the Humber Bay Arch Bridge. “I want to show you a particularly deceptive view of Toronto,” he urged, swinging me around to face the city skyline. Clustered next to the placid face of the Great Lake, the familiar shapes of Toronto rose into view: its high rises, construction cranes, windmills, and nestled in the centre with an air of coziness, the CN Tower.

“This is deceptive,” he went on, “because it appears from this angle that the buildings are facing us. But they aren’t.”

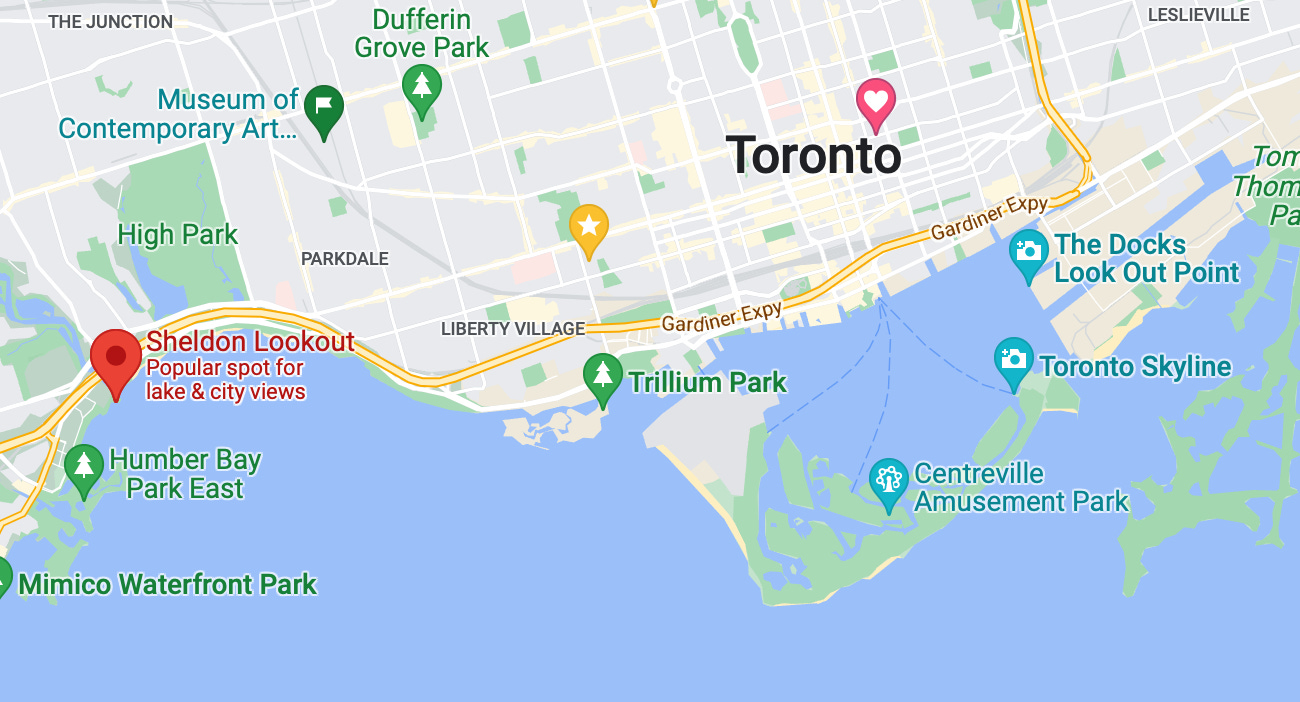

The lookout (red marker) in relation to the rest of Toronto. North is up.

“We are looking at the city from the side. The buildings are actually facing out, towards the water, from their perspective. And the crazy thing is—” (Here he pointed to the CN Tower) “—that is way further than it looks. It looks like it’s in the same plane as this other beach here, but it’s not.”

From this point of view, the city did look tame, almost like a miniature on a table. To the south, the bleached sky glowed over the clear water, the color fading centripetally from bone to a deep, intense blue. There, the horizon stretched and seemed to swallow us.

“Do you want to sit down?” (I felt like I was swaying.)

“Yes.”

We picked our way down to Sheldon Lookout, where I rested my bike against the bank and clambered onto a sloped boulder. Overwhelmed, I watched the swallows dive over and over into the water, cutting elegant loops in the air; further off, a black swan tossed its haughty head. Everywhere the brightness of the sky pressed upon me with a beauty so physical I almost felt it as a living pressure. I gulped down the minutes, unable to speak.

After some time, my friend pried open the silence with a question.

“Do you think, if you lived right here, you’d get bored of this view?” (He had settled onto a boulder somewhere behind me, cheerfully waiting out my trance.)

“No!” I said emphatically. Then I added, “I might get bored of the idea of it, and maybe not come as often. But if I actually showed up, I don’t think I’d ever get bored.”

He agreed and added that if he lived here, in one of the condominium buildings crowded against the shore, he would probably accept the view as part of the fabric of his life, like brushing his teeth. “I’d still enjoy it, but it would also be normal.”

I produced my phone to take a picture and he suggested there was no way I’d be able to capture what we were experiencing. I told him I knew that, that I just needed a marker for an essay I was going to write. “And I’ll tell them,” I added, “that this isn’t even close.”

This isn’t even close. (Sorry!)

Later, somewhere beside the Humber River, I asked this friend about beauty — about the brutality of beauty. Beauty had a way, sometimes, of troubling you with its vastness, with its unbroken placidity. One felt dwarfed before it in a way that was disturbing. Did he know what I meant? I was talking about the view, but I was also talking, in a slanted way, about my feelings for him — about the overwhelmingness of his presence that I had always felt since we had met, but had only grown in the last few days.

Where the sky was bleached, endlessly giving of itself, his generosity poured onto me in unexpected ways. Pastries, stories, facts, endlessly rattled out of him unstoppered — sometimes flowing so freely you wondered if your presence was even instrumental to their issue. He was always fatally absorbed in something or other, and left behind him a trail of topics exhausted: chess, math, the history of AI. Easily bored, endlessly drafting, spending time with him was like courting a summer rainstorm. It was impossible to feel prepared, or even anchored to solid ground. Being with him was like submitting yourself, willingly, to a surging flood of mind.

Image by Stephanie Syjuco.

“Beauty is… the promise of happiness,” Stendhal once said. For the longest time, this had been my favourite definition of beauty: beauty as a kind of lovely assurance. And I still don’t think Stendhal is wrong: this is the beauty of daisies in the summer, of a chubby-cheeked infant or the eyes of a wild doe. These forms of beauty carry with them something of the placid eternal, a sense that somewhere, things are exactly as they should be. But this is just one kind of beauty — one could say, this is merely beauty at its most tame.1

There is another form of beauty, one that has been written about both in religious texts and pop songs, as in Taylor Swift’s “Gorgeous” (emphasis mine):

You should take it as a compliment

That I got drunk and made fun of the way you talk

You should think about the consequence

Of your magnetic field being a little too strong

And I’ve got a boyfriend, he's older than us

He's in the club doing I don't know what

You're so cool, it makes me hate you so much (I hate you so much)Whiskey on ice, Sunset and Vine

You've ruined my life by not being mine

In the song above, it’s easy to argue that Taylor Swift is being cheeky with her negativity, almost using it as a flirt aid instead of as a literal description of how she’s feeling. And yet, I think there is indeed a literal reading of the song above, as anyone who has been deeply bothered by their own attraction can note: sometimes, a beautiful person can make you feel hatred. Not because you begrudge them their beauty or desire it for yourself, but because their beauty threatens to change your life.

In these situations — arguably what Donna Tartt also refers to when she writes that “beauty is terror” — we do not experience beauty as the promise of a divine realm where all is well. We experience it as a threat, as something so immense that all that we have built thus far, all that we have laboured over appears, as Thomas Aquinas once lamented, “like straw.” How can your silly life matter, after all, if up until this point it didn’t account for this? What meaning can your life possibly ever have had?

There is an existential vertigo that attends this kind of beauty; it seems to warp the very fabric of reality. Sublime beauty dazzles then, but it also blinds: in its power, it can actually injure us.

Art by SilllDA.

While my friend and I were together, it felt impossible to stop talking — and, too, impossible to say exactly how I felt. In the rush of discourse there seemed to be no room to address what was happening between us, or inside me. It seemed easier, as it likely always does, to debate the career of Chance the Rapper (Was it over? He: yes. I: no.) or Drake (Was he shameful? He: yes. I: no.) In this way we frittered away the time on a current of nerdy pleasantries and all the while I was burning beneath the surface with what felt, with every minute, less like desire and more like actual pain.

What did I even want?

Due to our sex-saturated pop culture but notably sexless lives, people of my generation like to imagine sex as the culmination of all intimacies that are possible between two people. What is rarely discussed, though, is the way in which even our desire for sex can itself be a desire to tame beauty, a way to defang an experience into something manageable and finite. It isn’t, after all, that my entire life will change (we tell ourselves): it’s merely that I’ll take on this lover, and in this way, I’ll possess the beauty, be greater than it. The beauty — as my friend said of the view — will become a part of my daily life.

But this kind of beauty cannot become a part of daily life. Its very nature threatens to rip apart daily life from within. And indeed, after my friend left I spun out into a manic frenzy. Moving from room to room I played Taylor Swift’s “Gorgeous” over and over, rock tumbling my thoughts until they lost their shape. I thought practically first: was there any particular thing I wanted, anything that would settle me again into my own life? Even if I were to communicate this, what would I even say? Then, socially: Would he resent me? Would it end our friendship? Was I about to commit a horrible faux-pas? Then, of course, psychoanalytically: what if this desire was problematic? Was I recreating some original traumatic arrangement, some doomed site of wounding? Even if I was, was there any cure now? Could there ever be a cure?

I went for a run (still looping the Swift); finished several pastries; swamped close friends with synopses of the past 24 hours. Outside, the sun curved lazily through the sky as though an infant were pulling on a circular calendar. Somewhere: the bark of a dog. Elsewhere: a woman laughing.

Evening, teeth chattering at my standing desk, I sent my friend a long text message explaining exactly how I felt. The message included the choice words “unlikely,” “there it is” and “that’s all.” Two hours later, he sent a message back explaining exactly how he felt. This message included the words “refreshing,” “but” and “thank you.” As I read it, the entire contraption of my anguish whooshed closed over my head and I was free.

Nothing was to happen between us — nothing romantic, anyway. We were, decidedly, friends in the most conservative sense.

The view from the Humber Bay Arch Bridge — later, at night, alone.

For days afterwards I felt flushed, but in a good way — as though I had been tossed around on a rollercoaster and survived. I felt our renewed intimacy, having shared such a perilous truth, but also the danger that that intimacy promised: as though I had narrowly avoided something awful, but getting close had been the point. It struck me that, even though he had not reciprocated my ardor, the mere experience of feeling it and communicating it had so derailed my daily life that I felt, against all odds, like I had been on some romantic escapade. All of the same elements were there, just not bilateral: the feeling of risk, of fear, of quivering not-knowing. The future, far from a promise of happiness, had briefly become a spinning maw from which angels and demons seemed to emerge in equal measure. And now that romance was impossible, the future had regained its terrestrial aspect. In it, there was cut grass, and chewing gum, and shadows on the pavement: the things of daily life.

What beauty was this, that seized me and let me down — beauty that does not comfort, but decidedly fucks you up?

“Do you think that there is a corner of this Earth that you could travel to far away enough to free me from this torment? I am a gentleman. My father raised me to act with honor, but that honor is hanging by a thread that grows more precarious with every moment I spend in your presence. You are the bane of my existence, and the object of all my desires.”

-Anthony Bridgerton, Bridgerton Season 2

The British poet HD once wrote about the relationship between truth and beauty thus: beauty was like a rose, drawing one down into truth. In this conception, beauty is a lure for the divine, a way of capturing attention in order to redirect it towards the substantial.2 If this is right, then the feeling of beauty must change as you travel down the stem of the rose, as you approach its source. Depending on whether you believe God is fundamentally pleasant (Stendhal) or terrifying (Tartt), beauty is merely a vestment for the dense beatitude within.

One reason I love this idea — and that’s all it is, merely an idea — is that beauty, for me, has never been purely pleasant. Nevermind avoiding as a young girl all doting around my own beauty; nevermind skirting as an adolescent the blandishments of advertisers and peers to learn the ways of makeup, haircare, fashion in order to better embody the feminine ideal; nevermind even as an adult now, being suspicious of my own desires to be near those I find physically beautiful. Physical beauty aside, I find even spiritual beauty to be disorienting: if I read this book in the Bible, if I let myself enter this mosque, will I be unable thereafter to return to the life I knew?3 Beauty has probably always seemed to me a threat of some kind.

And yet, despite these reservations, beauty reappears in my life. Again and again.

The other reason I like HD’s idea is that, given my persistent failure to ward off beauty and its risks, it enables me to interpret the return of beauty to my life as the return of the divine itself. In this reading, beauty isn’t a occurrence on top of the world — some sparkle or embellishment — beauty is a glimpse into the world as it is. Beauty is not less real than the rest of the world, then. Perhaps it is more real.

Wouldn’t that be something?

A close friend in college, resolutely Christian, knew this very well. Let’s call him J. J used to play the organ at Stanford’s Memorial Church; he was taking lessons from the chief organist and as such, had an antique skeleton-like key that opened the somber wooden gate that led up into the loft above the cathedral. He also had a key to the church itself. Some nights, practicing well past sunset into the warm California darkness, he invited me to come along, and I stood in the loft with him, staring over the immense, immovable wooden pews into the gargantuan darkness collecting in the apse. New-agey as I was even then, I was still familiar with the inside of the church, having performed there several times with the Chamber Chorale; all the same, with all of the lights off, baroque music bouncing ominously off the walls, shadows falling over the face of the angel holding up the stone lectern, the memory of an actual then-unsolved murder that had occurred here decades prior, I felt I was experiencing the space anew. This was an experience of beauty, and we both knew it — not because I was delighted, but because I was afraid.

J liked to tell me that God was infinitely more complex than we gave Him credit for, that the contradictions in Christianity were not their weakness but the proof of their very solidity.4 To prove this point, he often brought up the music of French composer Olivier Messiaen, which, to put it lightly, is terrifying. In Messiaen’s “La transfiguration de Notre Seigneur Jesus Christ” the choir moves between dissonance to greater dissonance, tossing the listener unceremoniously into a moving sea that threatens to swallow them whole. Is this a representation of evil? No: it is a representation of God Himself, or at least a glimpse of the grandeur of God.5 If, on one end of the contemporary Christian aesthetic, we have pastel portraits of Jesus, ahistorically white, gentle blue eyes filling with tears, on the other end is Messiaen, whose implicit argument is that any direct experience of God would so thoroughly fill and overrun our mortal senses that we would be pulverized by His majesty. Because God loves us, his music seems to say, He holds us back from the fullness of His being. He refuses to destroy us, despite how easy that destruction would be.

A biblically accurate seraphim by Dan Hillier.

I am partial to this interpretation of God, just as I am partial to the more brutal forms of beauty. Via the Sufi metaphor of the veil — literally, the hijab — that separates us from encountering God, I too feel a recurring urge to lift the veils around me in order to get closer to the source. Like most forms of compulsive risk-taking, it probably spawns from some originary flaw or maladaptive habit inside me, that I value my own sanity so lightly as to enjoy, on occasion, risking it for some higher-order experience. But maybe many of us share this flaw, because it seems so very human to long to be obliterated at the hands of something thoroughly beyond us. Almost as though we have some existential solitude that only the cosmic can cure.

As for my friend and I, we will go on being friends — perhaps with even greater insistence than before. In many ways, foreclosing the possibility of romance in this relationship is not a path to resolution, but its opposite. Because we are decidedly not lovers, not partners, and likely never will be, our relationship has an open-ended quality, partaking as it does of the infinitude that is underneath the best forms of friendship. The beauty has not gone away, and I hope it never does. Unable to be mastered, it simply coexists with me. Rather than “enjoy,” it might be better said that I suffer it by choice: I suffer its promise to continually change my life.

Gif source unknown.

Thanks for reading Chasing the Sundog, the newsletter where I tell you about the latest strange thing happened to me and we try to make sense of it, together. If you liked this post, you might like this essay on my time in Pakistan, or this personal essay on running in Toronto in the winter. As always, here is the complete archive of past essays. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Acknowledgements

To the person who inspired this essay, thank you for being my friend — and for being open to being written about. See you in our endless text thread.

Thank you also to David Mora, Gwen Hovey, and Daanish Shabbir who comforted me with grace, openness and genuine love as I careened — for a precious 72 hours — off the face of the known earth while I tried to understand what was happening to me. This essay is the result of my soul-searching, but the fact that I’m here writing it, reasonably well-slept, well-fed and loving towards myself, is due entirely to your care. I lift my glass to you, now and forever!

What’s more, I think this is the beauty of the “Beauty Industry”: it is the feminine ideal that so many women are encouraged to embody. To be themselves a promise of a future happiness, women must exude appeal and also the possibility of being tamed. They must be hard enough to glitter, but soft enough to yield. This is, after all, the beauty that is meant to comfort men.

There are other forms of feminine beauty, but they are more challenging. Lady Gaga is a wonderful example: she once explained in an interview that her aesthetic goal was to be both sexy and frightening, such that you were attracted and repulsed at once. Gaga, gorgeous as she is, does not promise future happiness. Burlesque and grotesquerie, perhaps!

This idea is from HD’s brilliant “Notes on Thoughts and Vision.” In it, she also describes her own experience of poetic inspiration, how she feels she has a mind in both her head and her lower abdomen, and from these two minds tendrils emerge and flow through the rest of her body — like two jellyfish, reversed into one another, I always thought. She was quote-unquote “discovered” by Ezra Pound in that, when he read her poems in the first decade of the 20th Century he immediately called her an Imagist and had her published. I see him now as an eager company recruiter, thirsty for a speck of a talent that was beyond even his comprehension. I say all this, of course, as a fan of her work.

This is about more than beauty, of course: it’s also about my own sense of agency, which is notably fraught. I wrote about a cousin of that here — parsing it in this essay as “laziness” or “underfunctioning” — but there’s plenty more to say about it another time.

Looking back, he was probably the most brilliant devoutly religious person I would ever meet, not because religious people are usually unintelligent but because even intelligent religious people tend to suspend their faculties of analysis, debate, skepticism when it comes to their faith. (I do not question this, by the way — I have my own sense of faith that I keep far away from my own skepticism by choice.) Still, it is a rare creature who reads voraciously the books of his own spiritual tradition, continually working through their divergences, and coming out strengthened not only in heart and spirit, but in mind.

Seen in this light, grace is God’s self-editing for us, sending His only son in the form of a humble human being: comprehensible! fleshly! The miracle, then, is not that Jesus loves us, but that His very presence does not destroy us — because, unedited, it could.

Stunning essay, Michelle ❤️

I love the idea of beauty connecting us to truth, to deeper reality. Not something lovely or pretty but something horribly more solid than we've been aware of. (I'm guessing JJ was influenced by CS Lewis' short book The Great Divorce?)

I like JJ's take on contraction as proof of truth, rather than invalidation. Indeed, Christians (& cynics perhaps more) often point out the stark contrast between "the old testament God" & "the new testament God". Modern Evangelical Christians, in my experience, view the new testament as a relief from the God of the old testament -- the horridness now resolved by Christ's sacrifice. Indeed, in modern Western culture, we can't imagine a God who isn't tolerant, un-oppressing, & smilingly from a glowing pale face.

But this feels, in larger part, like a taming of God, I'd agree with you.

God slides into our subculture, reclines with us on our couch, shakes his head sadly as we watch unruly protests on TV. Christians even ask, "Have you accepted Christ *into your heart*?" When in reality, the texts & idea that connect us to God reach like roots into things that we can barely survive, let alone contain within "our hearts".

Your words really get me thinking & feeling new things, Michelle. Thank you.

Intricate and compelling as always. I first read Donna Tartt's A Secret History tucked in the San Jaun Mountains of Colorado. I highlighted that quote and posted it to my Instagram. It has stuck with me ever since.