I was recently in a Szechuan restaurant with my parents and one of their 老乡 (lao xiang) — someone from their hometown. This woman — a matronly swimmer we often encountered at the public pool — had invited us to a local restaurant with a name that translated loosely to, “just grab a little something with your chopsticks.” Inside, the restaurant was blazingly cold, and at various tables families and/or friends talked garrulously over piles of steaming chili peppers. We had rabbit meat and a stew of silk gourd; I kept putting my chopsticks down on my rice bowl to wait for my tongue to regain a sense of life.

Szechuan is the region of China where my parents are from. It’s known for many things — including, according to an older Chinese man I met once, beautiful women — but it’s best known for its cuisine, which is irredeemably spicy in at least two different ways. There’s the classic kind of spiciness that most Westerners are familiar with, the taste of something painfully hot in your mouth that is measured with the Scoville scale. North American thrill seekers often chase this kind of spiciness through eating ghost peppers, Carolina Reapers, etc. Then there’s a spiciness that is often translated as “numbing.”

In Mandarin Chinese, the word for “numbing spice” is the same term that is used to describe the feeling both of goosebumps and pins and needles, like when your leg falls asleep: it’s a prickling pain that is broad but not deep. It coats you in its texture and crowds out all room for other feelings. This kind of spice usually comes from the Szechuan peppercorn, which, in addition to imparting this numbing quality to your mouth, also has a distinct floral taste.

It is the combination of both of these kinds of spice that gives Szechuan cuisine its particular way with you. It feels totalizing to eat it, you start sweating almost immediately — and the impression you get is less about volume of food so much as volume of flavor, as though the spices are ghosts that fill you with the idea of a feast as opposed to a real one. Hot ghosts on a bowl of rice.1

I’ll be honest — it’s not my favorite type of cuisine. I’m not one for super spicy food, and even though my recent romance with an unreformed pepper-chasing foodie has somewhat inured me to the charms of mouth-pain, I’ll be the first to tell you that left to my own devices, I happily gravitate to a bowl of congee or oatmeal. But on this particular occasion, I was eager to tag along with my parents, feeling as well the unmistakeable pull of our somewhat shared cultural heritage. (I also joked with them nervously, “When you order non-spicy food for me, we’ll tell everyone I’m adopted.”)

In the restaurant, our swimming buddy and her daughter ordered for us generously, and as the plates of food, some of them literal heaps of peppers, kept appearing on the table, they leaned over the table and chatted about life in the familiar, unrestrained way that my mother later told me was characteristic of her hometown. We heard about struggles with the border and with buying a home; missing China as well as the tensions inherent in wanting to return to a place of deep political instability. Husbands, friends and distant cousins kept appearing and disappearing as characters, like movie tropes in a film based on a distant life; I did my best to track the conversation over the drone of the A/C and through the thick Szechuan dialect of our friend.

At one point, though, I simply fell off the understanding wagon. My language was so limited that for much of the conversation, I was reduced to smiling and nodding, while periodically someone would turn to me and translate; I tried my best to ride the rhythms of intrigue in our friend’s voice, but ultimately was lost to them. I found myself then floating, as it were, in mental space: there but not really there.

It was at this point, at the apogee of my own understanding, that I heard something so familiar it seemed to physically reach out and touch me.

It was the song that had come on in the restaurant: “La Fama” by ROSALÍA and The Weeknd.

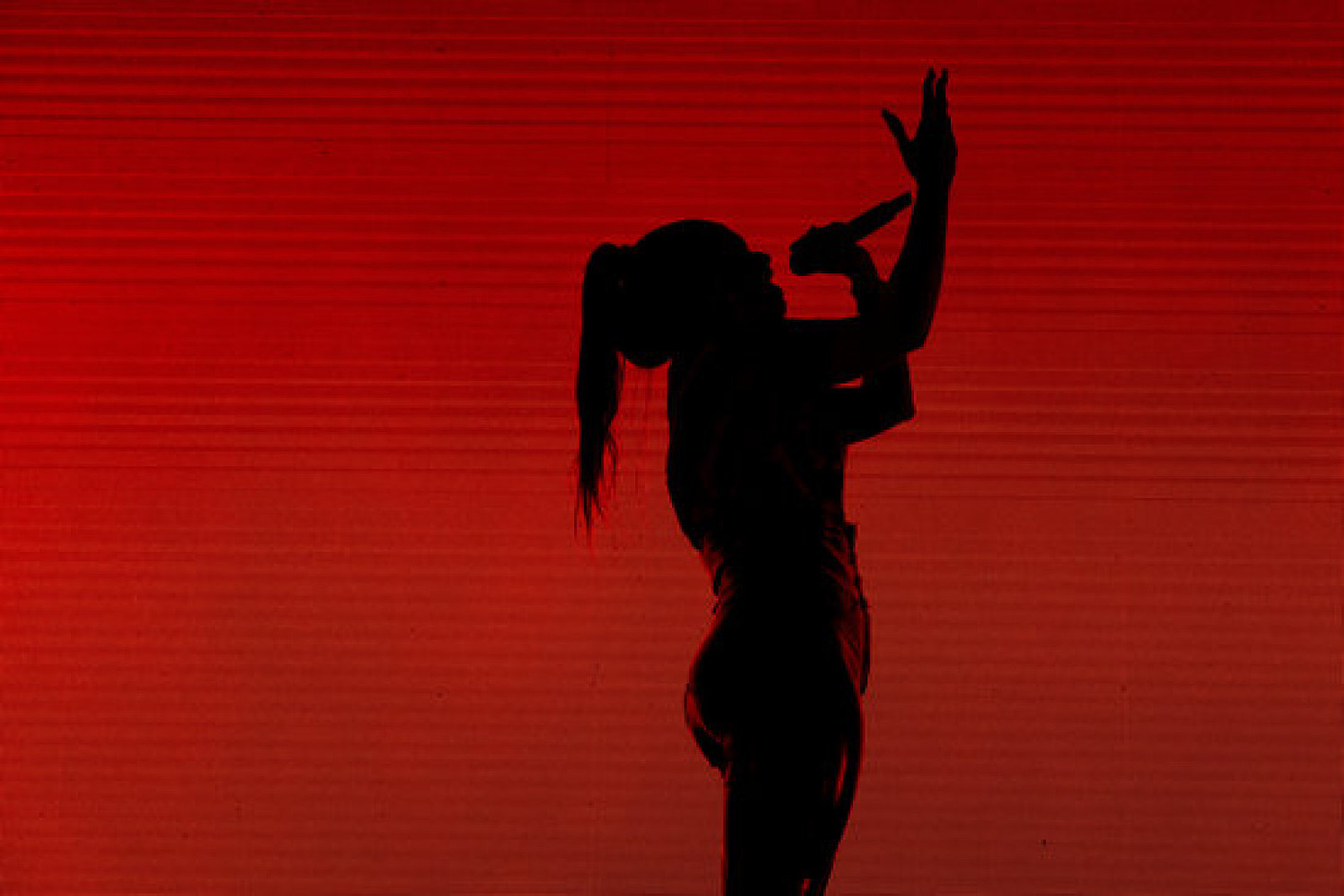

From the music video. ROSALÍA plays a club singer named “La Fama” (or “Fame”) who seduces and ultimately kills The Weeknd. You can’t say the club announcer didn’t warn him though.

“La Fama” is a brilliant song. Written in the aftermath of ROSALÍA’s meteoric rise to international fame from Catalonian flamenco singer to veritable pop star, the lyrics — translated from the original Spanish — describe fame as a “lousy lover” and a “back stabber who comes as easy as she goes.” The chorus admonishes the lovesick to go ahead and sleep with her, but “don’t tie no knot.” No matter how fame makes you feel, the song argues, she “won’t ever love you for real.”2

Lyrical insight aside, the song is just a banger. As soon as it came out in November 2021, I started listening to it, craving it, particularly its iconic opening instrumental line, a tight distorted horn over a flamenco-style beat. I wasn’t hearing this song for the first time in the Szechuan restaurant; I was hearing it maybe for the hundredth time. I could nearly sing it in Spanish.

Sitting there, tongue drenched in fragrant fire, straining to hear the gossip from a homeland I had never really been to, I had the distinct sense of being split inside myself — into the me I seemed to be (the placid daughter of these two Chinese immigrants from Szechuan) and the other me I felt myself to be (the one who knew what the Spanish meant, but couldn’t even make out the Chinese). I felt the ROSALÍA-loving me singing along to the words inside, like a little pearl wrapped in bamboo leaves that only I knew I was carrying around. Present but not, Chinese but not, me but not me, as there as I could muster.

I have this kind of experience a lot. It seems to punctuate my life, a kind of surreal out-of-body experience that I return to with unsettling regularity. If I were to put someone else’s words to it, I might point to W. E. B. Dubois’s sense of “double consciousness,” a concept that refers to the way in which African-Americans in the early 1900s were subjected both to an internal sense of self — for example, emphasizing to oneself the virtues of dignity and equality — and an inescapable sense of an external self: the way they were seen and treated by a racist white society. Dubois argued that this kind of “double consciousness” negatively affects the development of a coherent self, as one has no stable vantage point from which to determine the “true” self, as it were.3

Obviously, the conditions of my doubleness in the Szechuan restaurant were different from the original conditions referred to in Dubois’s work. For one, the external identity I feel isn’t as obviously structurally oppressive — though one could argue the construction of the traditional Chinese daughter is certainly more restrained than the construction of the progressive Third Culture leftist I play in the rest of my life — and for another point, I’m entering the external environment by choice. Part of what makes Dubois’ double consciousness so harrowing is its inescapable quality; pretty much all of society was (and still is) permeated by these ideas of who Black folks were supposed to be, and who they weren’t supposed to be. Me, I’m a plane ride or even a hearty drive away from being seen as the leftist freak I more comfortably am.

But I do resonate with the sense of slipperiness inherent to this concept, the idea that my own sense of self seems constantly to be interrupted by external conditions, and I cannot make myself unaware of the gap between how I see myself, and how others see me. What I lose, what all folks who have to navigate this doubleness lose, is the sort of naive oneness I imagine is part of the experience of holding structural and cultural power: when you tell the world who you are, it answers you. And most of the time, it agrees.

What must that be like, to be believed?

Sometimes I long for it, even while recognizing I’m probably just longing for a Pride Ad. Come out of the closet! After all, we are surrounded by exhortations to reveal our true selves, declare our true selves, project our one true being unto the world — and for the world in turn to celebrate us, affirm us, love us as we are. The great fantasy of Pride is that we even have a “trans-situational core” to be proud of – that is, a self that is the same regardless of context, that includes our sexuality and gender expression.4 Once we find our one true self, we are told, we must reveal it to the world so that we can be accepted into the world as we really are.

But what’s supposed to lie on the other side of this moment? Eternal bliss and acceptance in the maternal bosom of the world? Or at the very least, shunning the non-believers, a hot squad of queers all our own, our most beloved “shes, gays and theys” – our chosen family?

Of course we know this – of course we know this: it doesn’t always happen that way.

We want to believe the message of Pride because it’s gorgeous. Pride promises a dance that everyone is supposed to know the moves to, a dance involving disclosure and then acceptance. Pride even moralizes this dance, saying it’s fucked up not to do it. But if anything, Pride reveals the uneasy truth: that corporations are best at this dance, because the dance promises cash. And sometimes, in the places where we most want to be accepted – in our families, our intimate communities – the dance doesn’t happen at all.

And when the dance doesn’t happen, when self-disclosure doesn’t lead to immediate acceptance, we do have to choose: do we insist on being celebrated, holding our sense of wholeness above the norms of the space? Or do we let people see us as something other than we are – do we allow ourselves to slip into doubleness?5

I think what I’m trying to say is: when we moralize the story of disclosure –> acceptance in Pride, we cover up the very real mechanism by which acceptance happens in human cultures. Adjustment takes time, and it’s often painful, and it usually involves sacrifice and loss of old ideas and habits. Perhaps the reason we want it so quickly is because we’re timing it to how quickly a city can paint a sidewalk, or change the ad display in their window. Perhaps the other reason is that either choice for a queer person – to stand their ground or to slip into illegibility – is unavoidably vulnerable, and difficult.

So, Happy Pride. I know what I’m saying will sound a lot to some like I’m praising the closet, or at the very least praising the idea of being straight-passing. And I’m not trying to do either of those things. I’m trying to say that the closet, and/or being straight-passing, has been a reality of my life not because I haven’t come out, but because even coming out doesn’t guarantee you will be legible. It just means you have signaled your desire to be legible. It’s still a two-way street. And sometimes you still want to exist in rooms where you aren’t legible. What then?

Said in another way: in American culture, we think of the self as a private possession, something that we can then choose, unilaterally, to mercilessly project into the world. But what if the self isn’t our property? What if the self is fundamentally co-created, constituted by a dance of expression and recognition, theme and variation? If that is the case, isn’t it natural to have many different selves? And if some of these selves are not recognized as queer – not because we are surrounded by bigots but because culture takes time to evolve, and legibility is not instant – does that always have to be grounds for leaving?

I had to come out twice to my family. Once, by telling them. Twice, when I first dated a woman. Since then, having dated two men, I suspect the issue of my queerness has slipped again into lukewarm non-thought, though we’ve never really talked about it. It’s not that my family thinks that I’m straight; I think, deep down, they know I’m not. It’s that they have no language to account for what I am, and in the absence of this language, it’s easier for them to pretend there’s nothing that needs to be expressed.

Is this tyranny? I don’t know. I think, rather, that it’s a form of coexistence that is uneasy, but sincere. It sounds glib, but we’re trying our best. It’s not a dance, but I can still hear music playing, and we’re on the floor doing… something.

Hence the ROSALÍA song. Hence the moments of disjuncture.

Now, coming home to my conservative Chinese-Canadian city, I have moments of doubleness all the time: walking in, knowing full well people will see me as something I’m not, and I don’t correct them, and maybe they have small fluttering doubts, glimpses of a different kind of me underneath, but no one says anything. I exist as a kind of echo of myself, and some people hear it, but even if they do, they rarely say anything. The silence isn’t meant to be a punishment. It’s an expression of fear, of the fragility of the bonds that hold us together; it’s an attempt, however horrible, at creating something capacious that we can all live in.

The other reason I mention the “ghost of a feast” is that historically, I was told that Szechuan food originated both from having to keep warm in the winter and from the need for a cuisine that would go well with rice. Rice is cheap and bountiful, but meat and vegetables are not; spice is a way to enlarge the presence of the latter in order to make more pleasurable the experience of eating lots and lots of rice. Or so my dad has explained to me!

I hope I summarized this correctly; I’m summarizing off a summary :-)

But — I’ll just add that Claudia Rankine writes movingly about this experience in her indispensable book, Citizen. Dubois advances this idea in 1903 with his book The Souls of Black Folk; Rankine shows how it is still shockingly relevant in the year she publishes hers, 2014.

The sociologist Erving Goffman writes extensively about this, I am led to believe, in books like Frame Analysis and The Presentation of Self. Goffman argued — a la this summary Jonathan H. Turner — that the construction of the self was a dynamic, context-based process that could be understood as a “performance.” He did not believe that individual instances of someone’s self pointed to some essential “core” that was the same regardless of context.

All of this being said, I am of course operating from a place of enormous privilege to even have the choice of living a double life. There are forms of deviance that must be expressed, and cannot be hidden away; in such cases, as in the case of many trans folks, doubleness is a luxury they cannot afford. The world takes their being as a declaration, even when it’s not.

holy shit you can WRITE.

Another really thought-provoking piece, thank you, Michelle. You really made me think about how its *easy* to just be like, "BE YOURSELF, EVERYBODY PARTY NOW!". And then feel like you're progressive or fixing things. Thanks for bringing us to the murkier reality.

It was also very interesting to read this, because when you wrote "when you tell the world who you are, it answers you. And most of the time, it agrees." I was like, "wow, that's almost always my experience". I think it's a higher res view of what we often mean when we blanket something as "privileged". Saying who you are, & not really worrying if the world will answer with agreement.