For much of my time in the Bay Area — and certainly most of the years that counted — I lived with close friends in a house called Whale. The house, which was in a winding street in the Barron Park neighbourhood of Palo Alto, had been hand-built by our landlady’s parents in the 50’s; it had two ancient, gigantic oaks in the front yard and dark wood-panelled walls like the inside of a cabin. The kitchen had an adorable bubble skylight that in the fall would get covered in acorns and leaf debris; in the back there was a small curved window seat with a teal cushion, hand-sewn. At all times of day the house seemed filled with light — dappled, almost the quality of light at the bottom of clear pool. You would hear squirrels skittering on the roof above, and crows cawing in their nests; the surburban commuters in their sighing cars, the laughter of neighbours chatting on the street. And on top of all of this, as on a bed of warm noise, someone always seemed to be debating something: the political situation in India; the latest album by Ariana Grande; video-game based therapy; qi gong.

I was lucky in this, my first foray into any sort of self-serious project of adult living. I was lucky in that those years of my life were to come to represent, for me, a kind of interdependence that would seem to many North Americans a backwards fantasy, a sappy retrograde to the communes of the 60’s. For me, cooking and cleaning for and with my housemates, discussing seriously the problems of the clutter in the living room, the overflow of mail, communal groceries… this life became my proof that it was possible to have belonging without the bonds of marriage or standard rites of kinship. And as various housemates cycled in and out of our orbit — some leaving forever to move in with a partner — I remained happily installed at the house’s center, pleased to tend such a lively ecosystem. In those years, I was mostly in-step with myself, living in a way that did not require much persuasion. I felt I belonged to the house itself — to its sunshine, its silly smattering of arugula and wildflowers, to its honky-tonk piano and lush low carpets, its exposed ceiling beams spread over the main room like the ribcage of a great aquatic beast.

I live alone now, mostly. I spend some of my time downtown, and some of it with my parents up north in the city of my adolescence. My hours are mostly filled with Zoom meetings and/or the editing of various lecture presentations, documents, the occasional spreadsheet; I’ll write an email and send it quickly, text a coworker over lunch. As much of the professional infrastructure of my life is spread across two countries, two coasts, I spend nearly all of my working time speaking to colleagues in different timezones, making the uncanny approximation of eye-contact that is only possible in the parallax between two webcams.

As a result of all of this, I often feel exhausted — but it is an exhaustion that continues to feel unfamiliar. Unlike the satisfied prosaic soreness of the legs after a long run, or the tender-hearted sleepiness after a good cry, the exhaustion I’ve lately been navigating feels more like a software malfunction — the refusal of my conscious mind to continue working — though my hardware, the rest of my body, seems perfectly capable, even expectant. In this purgatorial state, I often feel split off from my own existence, bewildered at my own inner workings even as their consequences continue to play out: the 5 minutes of a “mind break” on Youtube become 20, 40, 60; the looming dread of an important deadline matched only by a fancy inner cocktail of anxiety and ennui. It isn’t that the work is difficult to do, or even that I am fully failing to do it. It’s rather that I have lost track of how my mind works, and what it means to use it well — like an athlete who is possessed by strange phantom pains, and every once in a while, must walk off the court in the middle of a match.

In my case, the phantom most often manifests as a glitch in my focus. In a meeting, sometimes even as a colleague is speaking, I will begin to feel my attention slipping, as though the slope of the conversation has suddenly become smooth and my mind can no longer find purchase. Then, I find myself craving sensory stimulation — the lighting of a candle, a quick spritz of perfume. Sometimes I pull out a stationery set and doodle; other times, I reach up and adjust the window blinds in order to bring in more light. I’ll open a window, or close it. I’ll turn on the space heater, turn it off. Depending on who else is in the room, I’ll either turn off the camera or leave it running, an unguarded window into my fluttering. In most cases, as I split my conscious attention between the texture of my lived environment and the digital conversation at hand, I am able to focus for long enough to be of use to my colleagues.

But indeed, the various fixes noted above are as temporary as they seem. The real cure is this: if I have the time and space, I’ll leave the house altogether and go for a walk around the neighbourhood. Then, immersed in a bath of the very world — its bustle, its unending hum — I find my mind is restored to its own rhythm, as though it was only ever a single voice in a great, complex polyphony.

I have a suspicion that some of my readers will render this essay through the lens of one of the most popular pop diagnoses of the day: ADHD. Perhaps nothing is so reflective of this time, of this singular moment, than the idea that young people seem eager to diagnose their own lapses of attention using a label designed by psychiatrists for a system often too formal to be of use. Eager for coherence in our experience, we raid the castles of the old institutions, borrowing language for our own purposes, sharing it, re-imagining it — and what emerges is an ecosystem of casual thought, identities half-made and cherished, exchanged as quickly as currency and vanishing too, like cash. It seems almost parochial now to claim that one struggles with focus and/or executive function without noting the possibility of “undiagnosed ADHD” — as though one has failed to do the basic required reading of the 21st Century.1

I am, however, suspicious of this taxonomizing instinct.

To be clear, there was a period in my own life when I was reasonably certain I had “undiagnosed ADHD.” I was so certain, in fact, that I set about doing the research to obtain a formal diagnosis, and was cowed by the cost — in the thousands of dollars! — of the various tests and examinations it would involve. Belayed by the financial and administrative prospect of all this, I reasoned with myself that so long as I wasn’t seeking prescription medication, it would be fine to simply treat myself as though I had ADHD, and consume as much advice as I could to manage the vagaries of my own attention. I read about the “wall of awful” that prevented one from beginning large tasks, about the importance of breaking projects down into extremely small steps, even of the importance of placing one’s dish cabinet close enough to the sink. Deeper investigations revealed biological interventions: zinc, magnesium, protein, exercise. Sleep, of course. Frequent breaks, a different rhythm of tasks. Habits, rewards, visual aids. For some time, I saw myself as an unusual animal who needed to be re-trained in order to produce for the world the appropriate lucrative tricks.

The problem was this: in owning the idea that I had ADHD, I had also taken on, albeit implicitly, a certain set of solutions — and the individual responsibility to carry them out. I was copping to the outlier condition of my brain, and promising to build my own attentional prostheses in order to function in a world that was, for the most part, running smoothly and without struggle. I was to believe that most other people did not have difficulty focusing, or executing tasks involving high executive function; I was to fix myself — and pronto! — for the sake of the machine of society and all of its quarterly targets. (I knew someone once who had worked for Elizabeth Holmes at the now-disgraced sham medical startup Theranos; she said that the message Holmes most often expressed to their team was, “Everybody else has it figured out. It’s just your team that’s underperforming. Get it together!”)

To frame a condition as a disorder, then, is also to accept an individuated view of a phenomena that may in fact be collective, societal, even political. It can be useful to embrace a diagnosis — one can use it as a linguistic marker for potential cures, advice, research, even community — but it can also be dangerous, because it restricts one’s imagination to a certain set of possible responses, many of which are individual acts of consumption or self-discipline.

Yes, I can better work with my attention these days — in many cases implementing the advice that I received for ADHD. But why is it that this advice is becoming broadly more and more useful? Why does so much advice about ADHD seem, in 2022, like plain common sense for a hybrid world gone haywire?

Lately, I’m not so sure that the language of disorder is truly adequate for what I have been experiencing — what so many of my friends have been experiencing. Instead, I have been seeking a broader framework for myself about how my mind works — and beginning to understand that the language of biochemistry — of dopamine receptors and certain gene variations — is far from adequate to structure our lives in meaningful, even graceful ways.

I’ll try to explain this by way of a practical example.

As I work throughout the day, on most days, my desk becomes messier and messier — in a physical sense. This is the natural result of the process I noted above: that as the day goes on, and as my meetings and my virtual work continues, I find myself craving different forms of sensory stimulation, each represented by an object, a tchotchke. As I write this now, my desk has on it a photo album of stickers, loose stationery letter sheets depicting a field of yellow dandelions, a box of cheap perfume samples, a hand-made to-do list (made of three different types of paper), and a stuffed dog. It is 10:30AM. As the day continues, I will likely add to this ecosystem of cozy chaos in any number of ways — with a book of poetry, say, or a small phalanx of snacks; with a music speaker or a candle, each element deliberately designed to add just the right amount of ambience, just the merest impression of a world beyond my work.

Here is a subtle point: the goal of these objects is not to divert me from the tasks at hand, from the email-writing and the lecture-designing and the research analysis. The goal of these objects is to create a world in which to do these tasks; in which foreground, midground and background resolve smoothly in a way that allows me to relax into my work.2 They are not meant, in other words, to become my focus — they form the backdrop that makes focus possible.

But how does one make sense of this kind of working — this kind of tiered attention?

I have had many periods in my life of understanding and misunderstanding my own mind. During one very influential period, I was enamoured with the idea of minimalist living: the idea that if I pared down all my physical belongings, down to the barest essentials, I would also pare down the excesses of my own mind — and discover, as Marie Kondo was always alluding to cattishly, the singular purpose of my life entire, somewhere between the stacks of books to donate and clothes that no longer brought me joy: a pearl of meaning all my own, prim for the immediate pluck. But this did not happen — not because I persevered through Marie Kondo’s multi-stage prescription but because as soon as I began to clean my desk, I found that it only aided my focus temporarily. I would sit in a happy, clean daze for an hour or two, and then by afternoon, I would find myself reaching for my little implements, for my feathers and my bits and bobs, and the process would begin all over again.

As I’ve aged, I’ve come to see this craving for texture — for more life, as it were — less as a symptom of an attentional disorder than a naive expression of hunger: a sincere plea from myself to myself for a different kind of experience.

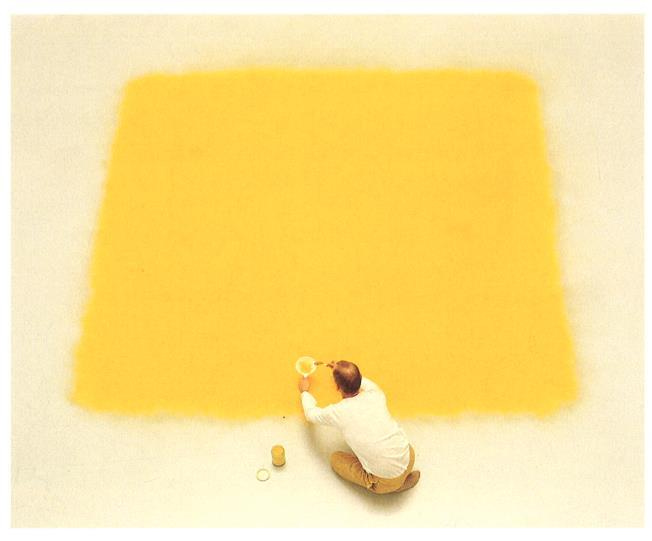

Consider this: the natural world is anything but minimalist, and yet it often profoundly relaxes us. Why is that? How can it be that a forest is the home to uncountable forms of complexity, to nested fractals at every scale, and yet we never find it overwhelming? Perhaps our office environments are in fact not distracting enough — neutered at the level of ambient happenings, disturbingly silent in the attentional soil. Perhaps what we need for our attention is not less stimulation, but more — the unending thrum of a busy world, somewhere just out of focus. (Even the cosmos, after all, has a background hum that never goes quiet.)

I think now of an early study on Zoom fatigue that posited its central mechanism thus: our brains are designed to process a certain resolution of visual information. On Zoom, we apply the same visual processing to the video feeds of our colleagues, but the feeds — being less rich in the sensory data that can be gathered in-person — are not quite adequate for a complete conscious picture. As a result, our brains work in overdrive attempting to find the missing data — straining to piece together a coherent image, both visual and social, of what is going on. (It is for this reason that audio calls can in fact be more restful — as audio feeds are more complete, and most importantly, they give our visual processing a break.)

Said in another way, we each process considerably more data than reaches our conscious awareness — this is why a new parent finds themselves waking immediately to the sound of their baby’s cry, or why the smell of smoke will interrupt your work session when the smell of dinner might not. Perhaps the attention glitches I’ve been experiencing have come from a level far below my threshold of consciousness — a problem with the richness of data my mind is designed to seek, a problem with being, on some level, attentionally deprived.

There should be a word for this — a word to describing the longing for “more life.” Let’s call it “reality hunger,” a phrase first coined by the writer David Shields in a 2010 manifesto on the future of the novel and representational art. “Reality hunger” I’ll define for my own purposes as “the hunger for the full richness of analog reality,” be that richness expressed in mere sense data or also in narrative, meaning, coherence: not just the texture of life, but happenings, events, moments of emotional significance. We want marriages, births, and deaths to be happening around us. We want to overhear that someone, at this exact moment, in this exact neighbourhood, has experienced something that will change their life forever.

When we don’t have reality, we crave reality, even produce it for its own sake. Thus Shields writes:

Our culture is obsessed with real events because we experience hardly any.

Thus when I hear a Harry Styles song, say the verified bop "Cinema," I’m no longer just consuming the music for the pleasure of dancing or nodding along, I’m listening to its lyrics — "I just think you're cool / I dig your cinema" — as a form of reportage about the actual man, Harry Styles, and his actual life, in which he's dating film director Olivia Wilde. I am consuming not just the melodies and the beats, but the sensation of hearing about another person, of hearing news of them, of their report of how they’re doing, because I used to hear those reports every day in the schoolyard and now to get even a semblance of that, I have to open Spotify. It's almost as though art has itself mutated to accommodate our general sense of being starved of reality -- with fiction becoming steadily overrun with auto-fiction, and so many great contemporary poets (like the cheerful anti-pedant Chen Chen) writing in a kitschy, diaristic style that would have seemed gauche just ten years ago. Disturbed by the relative silence, we have placed ourselves again in a digital village -- and we crave gossip not just for its pleasure, but because it anchors us to a world that seems, in all other ways, to be dissolving before our eyes.

For these and many other reasons, my years at Whale were some of the happiest years of my life — not just because my housemates were endless sources of good conversation, but because when even when I was sitting upstairs, tapping away at my computer, I could hear music through the floor. A blue mood in the air, the smell of dinner cooking. A sharp peal of laughter, even a sob. Life was always happening, humming along in the background — not merely a collection of sense data but also narrative impressions, snippets of story and plot, desire and its resolution. In this bath of life, it became more and more difficult to consider myself the protagonist — and, freed of the burden of forging meaning alone, my reality hunger sated, I could lose myself in my work.

Thus, the great poet George Oppen:

The self is no mystery, the mystery is / That there is something for us to stand on

Of course, I am not proposing an alternative to scientific understanding in this essay, nor attempting to come up with a better explanation for the recent rise in self-reported ADHD. Instead, I am interested in the ways new stories and ideas can unlock new ways of living — the way a myth about the sun would have helped our ancestors understand when to plant what, and how the seasons worked. I am fully aware that better explanations of these phenomena likely already exist, or perhaps are being created as we speak. But I am instead interested in weaving a web of meaning that can help me live better, regardless of how the truth-claims of that web hold up to scrutiny. Facts create the world we live in, but stories are what we experience, after all. Thus, “reality hunger” has become a powerful story for me — guiding me towards greater lushness, sumptuousness of living, and away from an ever-tightening trap of self-discipline that never resolves into ease.

Thus, I want us to consider in parallel the ways that the world that we live in, a world that is normalized by being both widespread and lucrative, is in fact an unprecedented experiment in deprivation. And that the ills that we hold in private may in fact be predictable outcomes of living in ways that are poorly adapted to the kind of animals we are. There may be no mastermind, no cackling tyrant behind these sanitized designs — there may only be a series of ill-advised utopic imaginings, a history of over-zealous visions that we could tune human nature as finely and accurately as any other machine. I will be the first to admit that I am a poor machine, but a very good animal. And I do not mind that. On the contrary, I have found that idea rather liberating indeed.

If you liked this essay, and you might enjoy this one on craving the presence of other non-human beings, this one on the American obsession with independence, and this one on a more somatic, body-based approach to living. As always, the full archive is here.

Discussion Questions

Feel free to reflect by yourself, with loved ones, with other readers in the comments, or in the weekly reading group hosted by mda.hewlett@gmail.com.

What is your relationship with your own attention/focus like? How has that changed over time?

Do you have, or have you ever considered yourself as having, ADHD? How has that label helped or hurt you?

Do you consider yourself more an animal or a machine? Explain.

It has become so stolidly vogue to claim the label of ADHD that the phrase “undiagnosed ADHD” has lately become more popular in my social circles than the phrase “diagnosed ADHD” or even just “ADHD.” It turns out that many, many young people on the internet feel a great kinship, perhaps even resonance with, the symptom list and life adjustments that come with this condition — but do not have the means and/or desire to obtain a formal diagnosis. As a result, I now hear and read about this regularly — and it has become a form of meta-ironic self-commentary to declare one’s “undiagnosed ADHD,” as this wry Gen-Z vulnerability is more likely than not to receive a circle of nodding heads and bemused “me too’s.” Far from being stigmatized, “undiagnosed ADHD” has now become the label for a very odd club of clever people, under-stimulated and stochastically social, flashing their trouble without ever quite allowing it to be touched.

Said in another way: if it were my explicit task today to “write 5 heartfelt, colorful letters to close friends” I would feel as paralyzed by that task as I do any other — assuming I was being asked to do so with undivided attention, without background or midground for my thoughts.

Your line about the slope of the conversation going flat got to me—felt loss and regret. There’s circumstantial evidence I had ADHD as a youngster, but life beat it out of me. Now it’s like a guilty pleasure.

aint it just the sines of the tvmes

big heart

I have adHd but its kinda a power at times like im allergic to some b.s. degree programs

:|