“We all have our truth of a place. There is no universal narrative of any city that is also real.”

— Sarah Thankam Mathews, All This Could Be Different

I recently read the “In My Feelings” Sundogg essay at an event in Toronto — a show my friends Z, C and I devised for the Danu Social House. At this event, called Long Boat Home, my new friend Z — Karachi-born poetess and sensitive soul — read from her upcoming book of poems while I sang covers and original tunes over my as-yet unnamed electric piano. The show sold out. C, our sweet fireball of a manager, had somehow managed to design a poster and marketing campaign so persuasive, the room ended up packed with amicable strangers: housing activists, collage artists, the occasional slam poet. We spent all of the ticket money on renting chairs. We paid the venue in drinks.

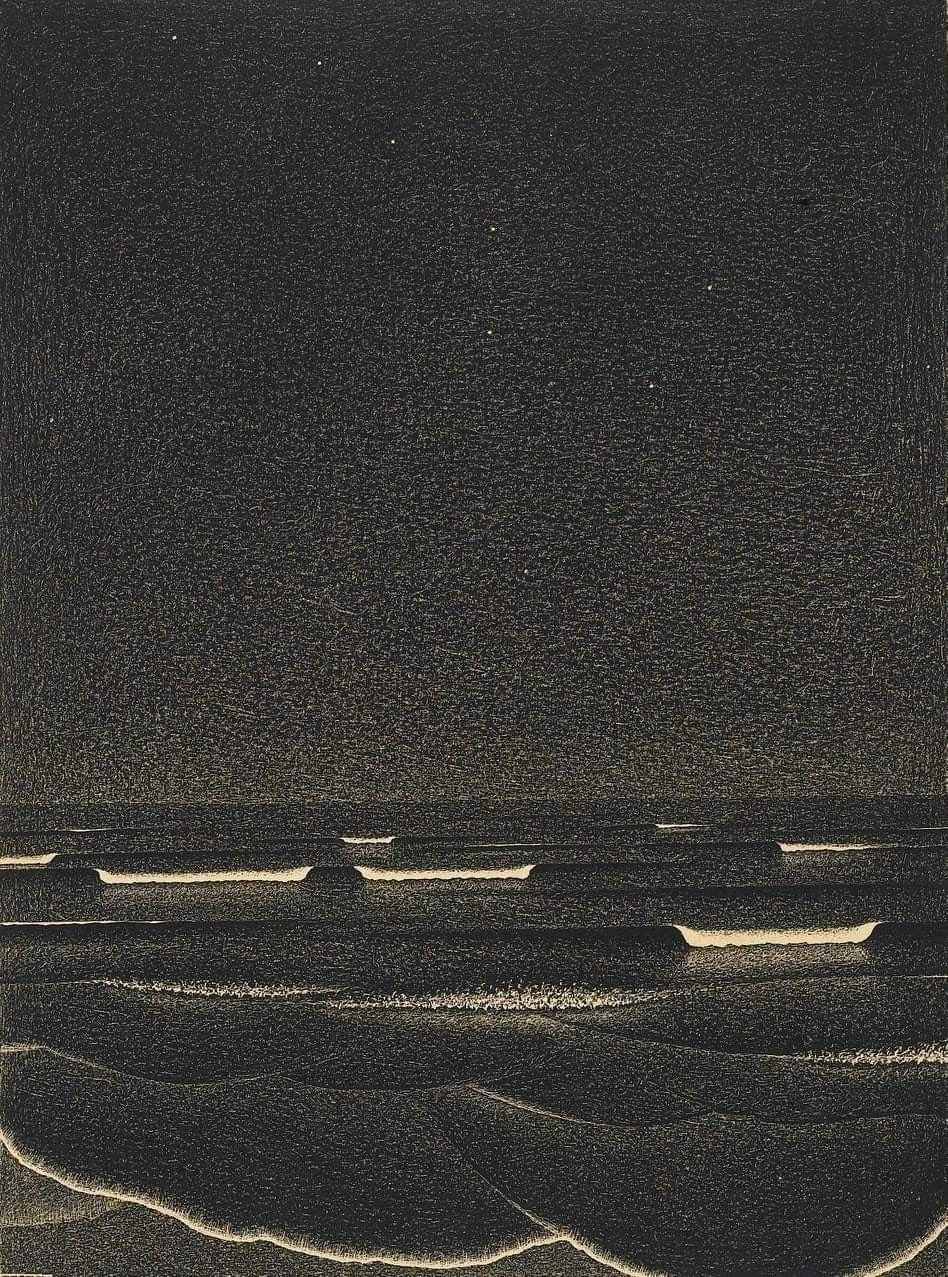

Before the show, washing my face in a basement bathroom sink, just having changed into a safari-green dress I had bought some weeks ago from friends at a West End thrift shop, I remember wondering about my life — about its shape, its significance. I was not an important person. I had one degree: a Bachelor’s degree, and in Comparative Literature no less. Devoid of formal titles, devoid even of a staged career path — I worked as an ethnographic researcher for goodness sakes — it seemed the rest of my life loomed before me, some fog-filled stretch of sand with contours so faint, one might have described them as suggestions. My parents had egged me on towards a graduate degree, even professorship. Or maybe: could I write a book, something definite and noteworthy? An exposé. A manifesto. A textbook on design research. I did not do these things. I washed my face in the basement of a friend’s bar, wearing clothes other friends had picked out from an estate sale. I climbed the stairs on shaky legs into a room warm with expectation. It was a Monday night in November. I read my essay. I sang.

On some level, I recognized that this event was my Toronto debutante ball — my way of announcing myself to the city as an artist who truly — finally! — lived there. By the time of the show, I had lived in Toronto for more than a year, but tentatively — like a plant without a taproot. Over that year, Toronto had been for me just a series of impressions: the bleak grey pavement of East Chinatown; the bright violets and marigolds of the Junction. The city had never quite resolved into a solid sense of place, most likely because I had not quite resolved myself into one who actually belonged there. I had not decided, in other words, if I was simply passing through, or actually building a life. In the context of this extended drift, this suspended intention, reading my essay at Danu felt rather like unfurling a reverse treasure map of all that I had been and discovered up to that point: the Bay Area, with its galleries mum and domineering; Paris, where an ex-partner ended things between ferns and hits of hashish.

Like coming home after a long trip, collapsing into the nearest couch, bags spilling — honey, you’ll never guess what happened on the ride! — it felt important to report on where I had been, my ten long years to my own Ithaca. As I read, I mentally collected every coin-scatter of laughter, every affirmative flutter in the audience as eagerly as one collects the sympathetic cooing of a lover to whom one returns.

Toronto is a very difficult city to describe — perhaps because one of its defining traits is its modesty, even its quiet conservatism. Here, Canadian politesse is perfected to a gloss, and it becomes difficult to differentiate between thoughtfulness (“Have a nice day!”) and avoidance (“Well, have a nice day.”) On one end, this modesty creates a city of monochromatic surfaces, strangers who smile but never touch. On the other end, this modesty creates space for immigrant, freak and sub-cultures to flourish unbothered — because, after all, it’s impolite to mind someone else’s backyard.

Thus, Toronto is a city that resists summation. More grid of petri cultures than promiscuous, sprawling ecosystem, one will find no zeitgeist that is not local, no cultural buzz or feeling with city-wide ambition, for any such shared vibe might too closely resemble a cultural overstep. Instead, one experiences sensorial flashes, brief and unrepresentative — an individual flock of tourists, eyes bright with marble-like innocence; the gruff impatience of a veteran merchant in Kensington. These impressions belong only to themselves, or to the neighbourhoods in which they are found; they are knitted into the larger fabric merely by proximity, sometimes by necessity.

It is for these reasons that I have in the past described this city as “slow.” Slowness here referring not to the people or to the culture — as a Southern slowness, say, or cooking a pot of something all day — but to an individual’s experience of place, to the process itself of place resolving into something definite. Toronto is slow because most of the city-dwellers I know who are happy with their lives explained to me that their first 5 years were miserable: friendless and confusing. Toronto is slow because the best parts of the city cannot be purchased, casually accessed or even stumbled upon; they can only be cultivated, painstakingly and with almost monk-like stubbornness. Toronto is a patch of dirt to be gardened in concert with others. Your favourite parts of this city, you will probably have to make.

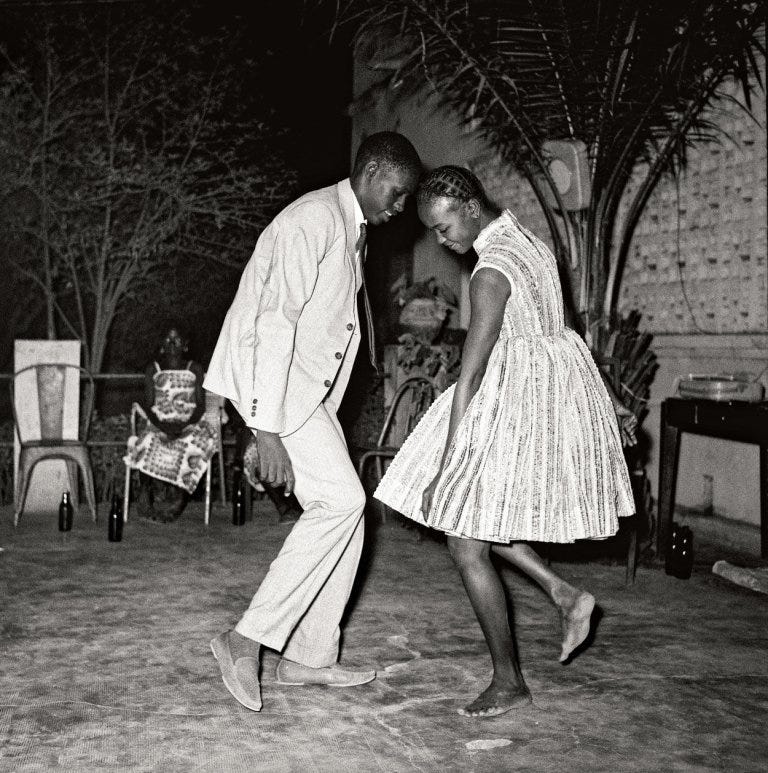

Finally, there is this, a cultural quirk so charming it seems almost old-fashioned: most Torontonians experience the city not as individuals, but as a part of a collective organ — through a cluster of friends, say, or family members: house parties, christenings, art events run by pals. “Community,” that vaguely omnivorous word, so oft-repeated in our new decade, is not a perk here — it is a requirement for entry.

To be clear: it isn’t that Toronto cannot be experienced alone; it is rather that everything that one can experience alone is of poor quality. One can pay an exorbitant fee to ride an elevator and look out from the CN Tower, or stare at dying fish in a massive aquatic maze. One can spend an afternoon on Bloor listening to couples murmuring over a Tiffany Watch. But such things are not worth the money or the time. It would be better to make some friends, friends who will cook for you a sour Vietnamese soup bejewelled with pineapple and shrimp (I see you, A). Better to befriend the owner of a bar, J who abandoned his Masters in Economics to mix drinks and peddle Parkdale gossip — and here he is now, stirring cream into your orange juice, soy sauce into your Coke. And then the pineapple noodle friend will come to your show and the bar-owner friend will host it. Better, then, to find the people you enjoy and then bump around the city in various configurations, watching their beloved faces in changing light.

My show with Z and C was called Long Boat Home because it was named after a performance piece I did in California.1 There, in a very different kind of collectivity, I exercised my very American right to be strange, even abrasive, in the name of capital-A Art. It is touching to me now, though, that even in the midst of that freewheeling period, it seemed necessary to christen my piece after a longing undisguised by cool. Long Boat Home. It is a very Canadian name: simple, unironic and warm.

At some point, on some level, one simply has to choose where one belongs. It is like choosing a life partner, I imagine: one sets down one’s bags, never fully knowing what it is about the other person that makes such a momentous thing possible. Is it their smell, or the way they kneel to speak with children? The way they call their mother Ma — or their stance on neo-Marxism? On some level, it is all of these things, or some heady mix of the aforementioned — and one will never arrive at a complete inventory, and this in and of itself is satisfying. What’s more, we are aware even as we make our commitments that all of these charming nothings might change. That one’s lover might develop a stoop, or an elderly stutter; that they might lose their taste for tennis and pick up a fancy for pickleball. And yet, we hope still that our bags will remain unpacked, that our coat will remain hanging by the door. That our pictures will stay on the walls and that our coffee stain will never quite wash out — because yes, we have decided, it is here that we belong. We belong because we have decided.

My last serious relationship ended, on some level — one level among many — because of a disagreement about Toronto. It is difficult to put into words, as so much about place and belonging is. Simply put, he said that the the TTC streetcars were slow — “like caterpillars, or worms.” I said they were charming, even wonderful — with their big balloon windows, their exorbitant interiors of curvèd ceilings and air conditioning. No, he said. They were worms. That was the beginning of the end.

I recognize that on some level, this conversation is hilarious — but it is hilarious, I think, because of how dense it is with meaning. One recognizes that the streetcar conversation is not just about the pace of public transportation, but about the question of loyalty, of pride, even of what it means to travel ethically. We had this conversation in his car, the same car which we had towed across the United States, from California to Detroit, in the back of an RV we had named — with our dear friend A, who owned it and travelled with us — Lilith Herschlag-Adkins-Jia. Chicago rap blared from the speakers, as it was always blaring, when he drove. We were somewhere on the East End, stopped behind a streetcar’s rounded red backside, coffee-starved and fighting — fighting because no amount of reasoning could change that cities choose us the way we choose them, and that we had each chosen and been chosen differently, and this meant we were soon to say goodbye, and no metaphor could change that.

I think now of a play I saw, at the peak of my loneliness after J. It was August, the hot night breathing everywhere, and they were putting on Shakepeare’s As You Like It in High Park. Shadowland had done the costumes and so these actors — many of them much younger than me — pranced around in oversized petunias, petals flopping into skirts. Above the two-storey set, a paper moon glowed with a blue so immense I felt it as chest pain. A singer-songwriter crooned during the set-changes, her voice transparent as melted sugar.

As You Like It moves between two main settings, the royal court and the forest — and of course, the forest is where the magic is, where kings sit on the ground to have picnics and love affairs can blossom outside of the traditional dictates of class and respectability. (If the courts are Lawful Evil, the forest is Chaotic Good.) There is an evil uncle, a few banishments, but the play — in the way of all classic comedies — ends with a quadruple marriage. There is a sense, too, of civil restoration: that now that we have found our unsuspected gems in the wild, we can return to society, and take up again our worldly posts.

This mood of blissed-out triumph pervades the ending of the play for all except one character, my favourite: the melancholic Jaques. Jaques declares — in the midst of the marital glee of the other characters — that he is not to return to society, but instead to remain in the forest as a hermit. The famous “All the world’s a stage” speech, so removed it seems to come from an omniscient narrator more than a character, is his. And he ends the play with the following lines, proclaiming his commitment to a different kind of life:

So, to your pleasures:

I am for other than for dancing measures.

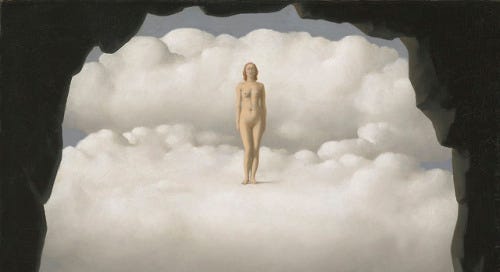

Jaques, an exiled nobleman, has no love interest and no interest, either, in love — instead, he perceives the settings of the play backwards, as it were: with the forest as a home, and the court as a temporary sojourn from the truer vicissitudes of life. Unlike the others, he believes he can make a home in the forest, where all is subject to change and one can find no shelter in courtly gain.

I was happy to watch this play, standing far back in the nosebleed seats, surrounded by young families and couples touching heads. But if it weren’t for Jaques, I would have felt doomed. His is the path I’m on. There is no marriage, no sanctioned coupling that will resolve his life. Exiled, removed, but also deeply committed to the place where things are always changing, I understood his example as one who makes a home of chaos, who decides to be a permanent outsider. He belongs to the forest not because it has made any promises — but because a home is what we have in the absence of promises. You put down your bags where you do. And that is enough.

It will be good to live this next part of my life, rooted in a place. I recognize that in some sense, I am “settling down,” though with none of the markers that traditionally indicate such a process: permanent housing, a partner, plans for children. I am instead like a bohemian bird, “settling down” into the colourful nest of a kleptomaniac. I will be someone’s odd neighbour then, the unmarried artistic aunt. But in another sense, this is exactly why one lives in a city: because there are many, many ways to be of use.

It would be nice to write an apologetic essay for once — one defending my life choices the way religious scholars defend the idea of the Holy Trinity. Such an essay would be filled with jokes, and caution the reader against the indecent peril of living too narrow a life. Study the liberal arts! Do strange things! Listen to Alan Watts! (I wonder if you, dear Reader, can even sense such an essay now.) But I am not in the business of justifying the vagaries of my late-twenties, the travels and windings that brought me here. I am merely looking backwards, and reporting on what I see: the slow ooze of an artist’s life in a curious city. I am looking backwards because to look forwards, for now, is impossible.

But, it is a pleasant impossibility — proof, I suppose, of a life founded on questions. I am grateful to have had the privilege to live my questions — and for such questions to have led me to this place.

If you liked this essay, and you might enjoy this one on California, this one on Pakistan, and this one on coming home to the Earth itself. As always, the full archive is here.

Discussion Questions

Feel free to reflect by yourself, with loved ones, with other readers in the comments, or in the weekly reading group hosted by mda.hewlett@gmail.com.

Where do you live now? Have you put down your bags? Why or why not?

Think of a place, relationship, or other life decision that you have seriously committed to. Was there a moment or realization that helped you commit?

Try to describe the place you live now, as though to a stranger who has never been there. What makes it different from other places, both good and bad?

Acknowledgements

C, I don’t know how I lived so much of my artist life without you. Thank you for your generous spirit, your zest for getting things done, your exacting and excellent taste, and your hot-as-fire email marketing. It was an honour and a pleasure to be managed by a friend!

Z, my soul sister, birthday twin (!) and Sensitïve other half. I hope your upcoming travels bring you great insights and many new writerly ideas. I have more thoughts I can’t put into words but I trust you know how magical our collaboration has been. I’ll see you very soon.

J, I’ve never been so glad an economist quit their job — and that’s saying something. Your bar has been my refuge and I don’t even drink. Thanks for trusting us, and for trusting me with your space. It’s a good one!

I have always loved this name for its charming ambiguity. What is a “Long Boat Home?” Is it a long boat, headed home — or a boat ride that takes a very long time? Are we remembering the journey that brought us here — or are we on the boat as we speak? And tell me: do we ever get there? Are we ever not going home?

I moved every couple years growing up, then again when my husband and I were deciding where to live. Now we’ve lived in Utah eight years, longer than anywhere else. We have put down our bags, and yet now we’re itching for the wilds, wondering if we can be rooted while also reaching, wandering, traveling the world but still with a place to come home to. Thank you for this beautiful piece!

I was lucky enough to be in the audience at Danu. Blown away by your singing (your voice!) and essay and warm charisma. The first cover of 'Not' I've ever heard, and one I want to hear again and again. Toronto's lucky to have you here.