Lucid Dreams of the Early Internet

How can we build a collective future without a collective past?

I have nostalgia about the early internet. A lot of 90’s babies do. The internet in its early public days was somehow both shameless and intimate, a calm sea dotted with strange little islands. Geocities blogs and word-art lists, glittering gifs and animated backgrounds. Heck, sometimes when you visited a page, an Enya song would start playing. You’d click a hyperlink and your cursor would turn into pixel-art of a cherry, your scrollbar baby pink. You’d scour your crush’s Angelfire blog for secret links, hoping this time, the image of his favourite band (Augustana) would lead to one more page, one more tender act of self-disclosure.

I think creative freedom thrives in this kind of middle ground between invisibility and hypervisibility. If you believe no one will ever read your blog, it’s fun for a moment but eventually you lose steam. The beautiful things take on a kind of stagnancy, even sadness. What’s the point? On the other hand, if you are creating in hypervisible conditions — say, on Instagram or on Facebook, depending on your follower count and settings — that act of creativity can so easily be cannibalized by a broader performance of who you are supposed to be. How should I be? What do these people want from me? What would I post? Once you start asking such questions about yourself in the third-person, seeing yourself from without, you lose touch with the part of you that’s actually creating, sniffing out the next sentence, brush-stroke or movement in the dark room of the not-yet-made.

For a moment, for me, sometime in the early aughts, somewhere in the world of teenage blogs and basic HTML, CSS and PHP, this balance between visibility and obscurity was perfect. I knew what I was creating could technically be viewed by anyone with an internet browser, but I also knew that no one was stumbling over my page by accident. I shared the URL with friends and hoped it would leak outwards, to my crush. I left easter eggs and imagined strangers finding them.

What was even on my website? I honestly don’t remember. I probably had lists of the things I liked: rock bands, novels, anime. I could be misremembering, but I might even have had a list of my friends, but their AOL names, like *~chuchu~* and Kota. Some of these friends I knew in real life, others I knew through online roleplaying games and forums, like Gaia Online. It felt thrilling not to make the distinction, just as it felt thrilling to be able to change the background with a few lines of code. Unlike in real life, where my construction of self was mercilessly filtered through a grid of family—school—society, my online aesthetics had immediate declarative power. On my site, I was who I said I was. There was no one to disagree.

Image by Fanny Papay. Discovered via Carolyn Pokorney’s Are.na channel.

This mood of freedom expanded beyond the personal and into the collective, too. On the early internet I was already talking to adults on various forums, folks who, looking back, I definitely had no business conversing with the way I did. Under the forum name “Serafina” I practiced racking up points for posting on Saltcube, a BBCode forum focused on lucid dreams, out of body experiences, and astral projection. There, I learned about the telltale signs that you are literally in a dream:

Do your hands appear shadowy, strange, and oddly long?

Do your light switches and appliances not work?

Is the time on the clock stopped?

Conventional wisdom among Saltcubers held that it was difficult, but not impossible, to enter a dream fully aware. More common was the route where you fell asleep, began dreaming, but somewhere along the way, realized you were in a dream and shifted into lucidity — kind of in media res. The signs above were some of the things you were meant to check for, not just while sleeping but in waking life. In order to have lucid dreams, you had to begin by strengthening your awareness of the distinction between waking and dreaming — a distinction that, as it turns out, is often disturbingly murky.

Today, if you want to learn how to lucid dream, there are plenty of listicles on the other end of a Google search. These listicles even cover a lot of what we were discussing in the early days on Saltcube, but they read as kind of scrubbed to me, a sanitized, corporate-friendly version of what it means to be interested in lucid dreaming. In the same way that meditation — or “mindfulness” — has been scrubbed of its varied and historical ties to religion, visualization and supernatural ability, lucid dreaming has been scrubbed of its ties to the occult. Yes, you can learn to lucid dream without being interested in astral projection and out-of-body experiences (OBE, as we called them on Saltcube). But, I would argue, it’s a fundamentally different experience.

Some things likely not mentioned in contemporary articles on lucid dreaming:

In order to astral project, begin by lying down in your bed, preferably on your back. Close your eyes, and deliberately, in as vivid detail as you are able, begin to imagine another room inside your house. You are inside this room. What does the light look like? Go over to the desk. See all of the objects on the desk, exactly as they were when you last saw them in waking life. Begin to pick up every object, feeling its texture, weight, temperature. Hold them in your hand until they become solid.

Or this:

The boundary between your body and the rest of the world is semi-porous. As you are falling asleep, but right before you go under, begin to push your consciousness — headfirst, never feetfirst — upwards, as though you are sitting up in bed. At this time, you will likely hear a loud, whooshing sound, as of warm television static. The body will attempt to pull your consciousness back so you will have to exert force in order to free yourself completely, down to your toes. Do your best to pull yourself out from your own body. Some like to run the following check: turning back, can you now see yourself sleeping in the bed?

All of this feels like a fever dream to me now. Not just in the sense that the knowledge itself seems suspiciously specific, possibly based on a theory of the universe that confuses experience for objective reality, but more simply, in the sense that I have no one to share this with in my daily life. Who were those people I spoke with, and where are they now? If I wanted to meet them, where would I even go? My months, years spent on Saltcube have no anchor in a collective past I can refer to, beyond some vague gesture backwards to an “era of BBCode forums” or “internet communities preceding Reddit.” How is it that, at 27, my experience of adolescence already feels appropriate for a museum?

Image source not found. Found via Hunter Priniski’s Are.na Channel.

If Geocities allowed us to sample the intoxicative delights of self-fashioning, Saltcube had a collective ambrosia all its own, a utopian idealism that seems, retrospectively, both absurd and deeply authentic. The feeling was that, now that the internet was able to connect weirdos from all the corners of the globe, we would now be able to achieve things that were impossible before. All we had been missing was each other. And now that we were connected, anything was possible — like meeting up in dreams.

And in fact, one of my most vivid memories of my Saltcube days was stumbling across a thread of two forum friends — presumably, who had never met in real life — agreeing to meet in a particular space and time in their dreams. The target location was somewhere like the moon, except once one of them arrived, they realized it was covered in grass. Were you there? Did you see that too?

Yes — I was there. I saw that.

There is a particular unsettledness I have now, in relation to these memories, that I think has to do with the fact that they feel so unmoored, so divorced from the rest of my life. Because they never happened in a physical place, there is no place I can return to, no way I can retrace my steps in order to find others who experienced the same thing. In this form, memories can appear across the years like fakes, or fragments of some fictional interlude in my actual life. Did I really spend time on this forum, or am I just imagining it? Who’s to say for sure?

What’s worse, the seed of that collective utopia has since been planted and thoroughly played out, such that we are all now in a state of disillusionment about the virtues of connecting strangers on the web. After all, this is the really dangerous idea that’s created the internet we know now, which is that if you just focus on putting people in touch with each other, amazing things will happen. Connecting strangers with shared interests as an unalloyed good? Sounds wonderful, as long as those interests aren’t conspiracy theories, pseudo-science or literal plotting of mass attacks. Today, the idea that “connectivity = good” seems naive, if not downright evil; at the very least, it too feels like an artifact for a museum, representative of a time when a bright-eyed Zuckerberg had not yet seen the inside of the US Capitol.

Of course, not everyone is equally disillusioned. Even as I write, there are still tech founders who haven’t yet given up on the idea of connectivity, like the housemate I had once whose entire startup was focused on the idea that better forms of collective knowledge would solve complex problems like curing rare cancers, or climate change. The idea was that X is in X’s head, and Y is in Y’s head, but if these puzzle pieces just came together, we’d have the whole picture.

Unfortunately, I’m deeply suspicious of this idea. For one, I don’t think knowledge works as my housemate imagines, in a clear explicit form with obvious boundaries. If anything, what we call knowledge is usually unworkably fuzzy, blurring fact with opinion with inference, constantly shifting with our mood and ability to communicate. What’s more, often the most valuable forms of knowledge need space and work and emotional safety to be articulated at all. And these articulations in turn require more than a technological interface: they require trust, understanding, patience, and during all of that wildness — which no app can make frictionless — what is keeping you committed to staying?

Saigon in the 90’s. Discovered via Quynh Nguyen’s Are.na Channel.

The German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin liked to suggest that a utopian socialist revolution would be preceded by an aesthetic return to the distant past. He was convinced that any future collectivity would have to be grounded in some shared historical vision, even if that historical vision was imagined. What mattered was that it had to be evocative, and shock us into the present, into “exploding the continuum of history.” We had to become aware of our role as writers of history, not merely as empty vessels for receiving some pre-determined timeline.

I like this idea a lot, not only for its promise that collective action is possible, but also for its implicit suggestion that nostalgia is incredibly powerful when shared. When we dream of a distant past together, however constructed that past is, we build our staying power for negotiating the present: our ability to converse, argue, and actually knit our knowledge together in a way that benefits all.

Looking back, this is what I loved the most about the early internet: the way in which it was so conducive to dreaming, generosity… the way in which strangers helped one another and offered so much, seemingly for nothing in return. We did not yet have a collective past, but we were building one, day by day. It only seems to me now that at the moment when we could have used it, a great flood swept it all away and we were left wondering what singular enchantment we had all just experienced.

When creating meeting places on the internet, we have a responsibility to imagine people well. Are people containers for puzzle pieces of knowledge, waiting to be connected? Or are they something stranger than that, something unformed and becoming, something that needs dialogue, pushback, experimentation to even become real? When we emphasize mere connectivity over collective doing and meaning making, we elevate platforms that offer increased connectivity at scale. But at every leap from platform to platform we lose the intricate ecosystem of meaning that was built before, and with it, its potential for collective action.

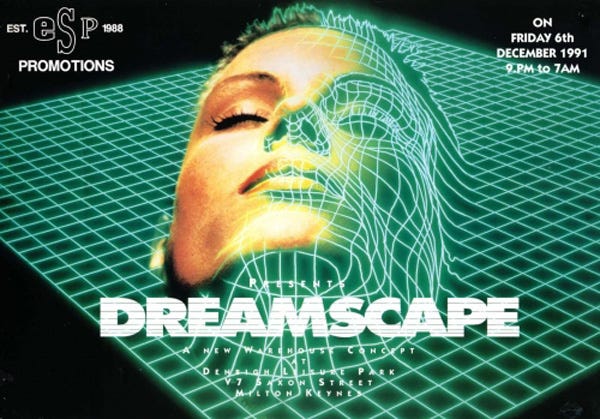

A poster for a 90’s rave. Image found via Noah Suppin’s Are.na channel.

In lucid dreams, the power of suggestion reigns supreme. If you want to fly, you just sort of… think about flying, and it happens. It’s not instant — there’s often a strange delay, like a lag in your own processing power — and it’s characteristically disobedient to means. You might want to fly, but find yourself swimming breaststroke through the air. You might want the wings of an eagle, but find yourself wingless and floating. Almost anything is possible, but you have to give up total control. In this, and many other ways, lucid dreaming is very much like collective action.

There’s one other thing about lucid dreaming that tends to surprise beginners. It’s the fact that, if you haven’t experienced something in real life, or have no references for it, it’s nearly impossible to experience it in a dream. A dream operates like a pastiche of previous references: things get remixed, but the objects themselves must be fundamentally familiar. This is why it’s easy to dream of a lobster that’s also a telephone, but not to dream of an “ideal lover” who you have never met before. Dreams synthesize the way collages do. To experience something fundamentally new, you usually need others.

The first time I had a lucid dream, I used Saltcube techniques. Unbearably excited, I ran through my “lucid dream bucket list”: I met some favorite fictional characters, went flying, tried to turn on a few lights and was delighted when they didn’t turn on. At the time, I was in love with someone in real life who did not reciprocate my affections. Perhaps, I thought, I’d go visit him, go by his house — the only problem was, I had never been to his house before. I didn’t know what neighbourhood he lived in, whether he had a driveway or a balcony, a sweeping front lawn or a little square of grass. Nonetheless I tried. Take me to his house, I thought into the dream.

I still remember this as though it were yesterday. For some reason, I was on my back. The air was cool and rushing over my face. I was on the highway, the orange lamps rushing by as I travelled, on and on, getting closer with every moment, and yet never arriving. Because my mind didn’t know where I was going, I wasn’t able to take me there.

I was on the highway for what felt like ages. I never did meet the man I wanted to see.

Were you there? Did you see it too?

Thank you for reading. This essay is part of an ongoing writing project in which I take a magnifying glass to small things in culture and try to learn about us in the process. If you liked this piece, please consider either subscribing for free or sharing.

Subscribers get a new essay to their email inbox every week, free of charge.

If you liked this, you might also like these: The Beauty of the Ice Runner, which is on slowness in design, and Knots and Bubbles, which is about my travel in Pakistan and what I learned about culture there.

See you next time and please take care,

M.

Bravo, Michelle. Everytime I read & re-read this part I start tearing up, it's tapping something deep inside me, something that synthesizes a big part of your argument in a way words can't.

"I still remember this as though it were yesterday. For some reason, I was on my back. The air was cool and rushing over my face. I was on the highway, the orange lamps rushing by as I travelled, on and on, getting closer with every moment, and yet never arriving. Because my mind didn’t know where I was going, I wasn’t able to take me there."

I this sort of spiritual/social level critique of "connectedness" is incredibly rare. Keep writing & opening our minds, dear friend.

This is stellar, Michelle. Lucid dreaming and astral projection has always fascinated me. Bashfully, I think of this quote from J.K. Rowling's final HP book: "'Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on earth should that mean it is not real.'" I have daydreamed so long and extensively the word daydream is insultingly inaccurate. I like the thought that everything we can see was once a thought or the object of someone else's thoughts. I think we undervalue the significance of dreaming to no end, with no goal in mind, just creatively idle.